Cardiac ablation is a medical procedure used to treat heart rhythm disorders (arrhythmias) by stopping the source of the abnormal rhythm. The aim of the procedure is to help the heart beat in a more regular and stable way and to reduce or eliminate symptoms caused by the rhythm problem.

Cardiac ablation does not involve open-heart surgery. It is performed using thin tubes called catheters that are guided to the heart through blood vessels, most commonly from the groin.

- When Is Cardiac Ablation Recommended?

- Preparing for Cardiac Ablation

- What Happens During the Procedure?

- What Will I Feel During the Procedure?

- What Happens After Cardiac Ablation?

- Recovery and Daily Life After Ablation

- Medications After Cardiac Ablation

- Risks of Cardiac Ablation

- How Successful Is Cardiac Ablation?

- In Summary

When Is Cardiac Ablation Recommended?

Cardiac ablation is considered when an abnormal heart rhythm causes symptoms, affects quality of life, or continues to recur despite medication. It may also be recommended when medications are not well tolerated or when long-term rhythm control is an important treatment goal.

The decision to proceed with ablation is individualized. It depends on the type of arrhythmia, how often it occurs, how severe the symptoms are, and the overall condition of the heart.

Preparing for Cardiac Ablation

Before the procedure, several evaluations are usually performed to confirm the diagnosis and ensure the procedure can be done safely. These may include heart rhythm recordings, imaging tests, and blood work.

You may be asked to stop or adjust certain medications before the procedure, especially rhythm or blood-thinning drugs. Fasting for several hours before the procedure is usually required. Your medical team will provide clear, personalized instructions in advance.

What Happens During the Procedure?

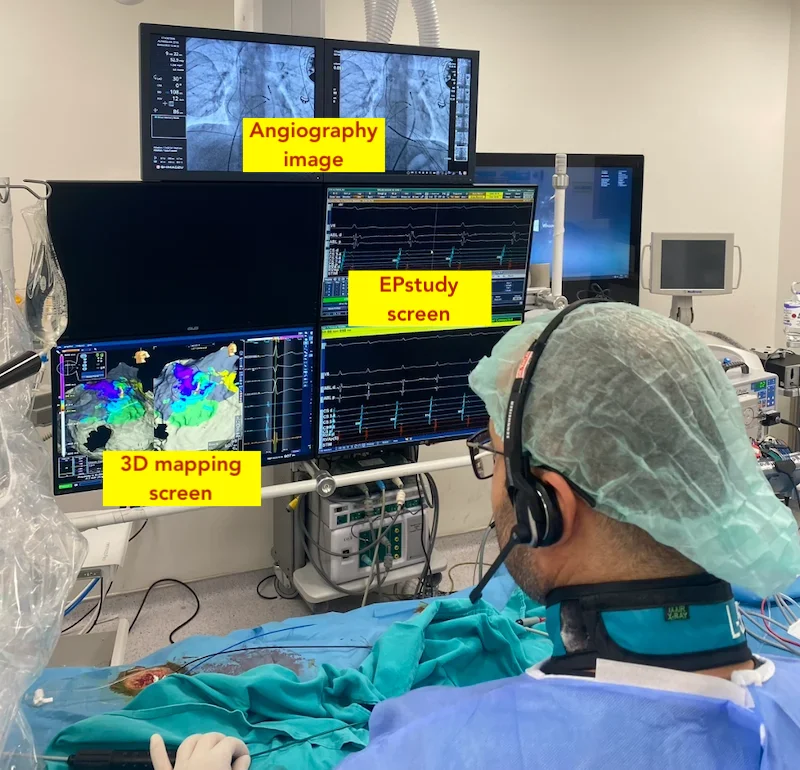

Cardiac ablation is performed in a specialized hospital unit. Most patients receive sedation, meaning they are relaxed and sleepy, and some procedures are done under general anesthesia.

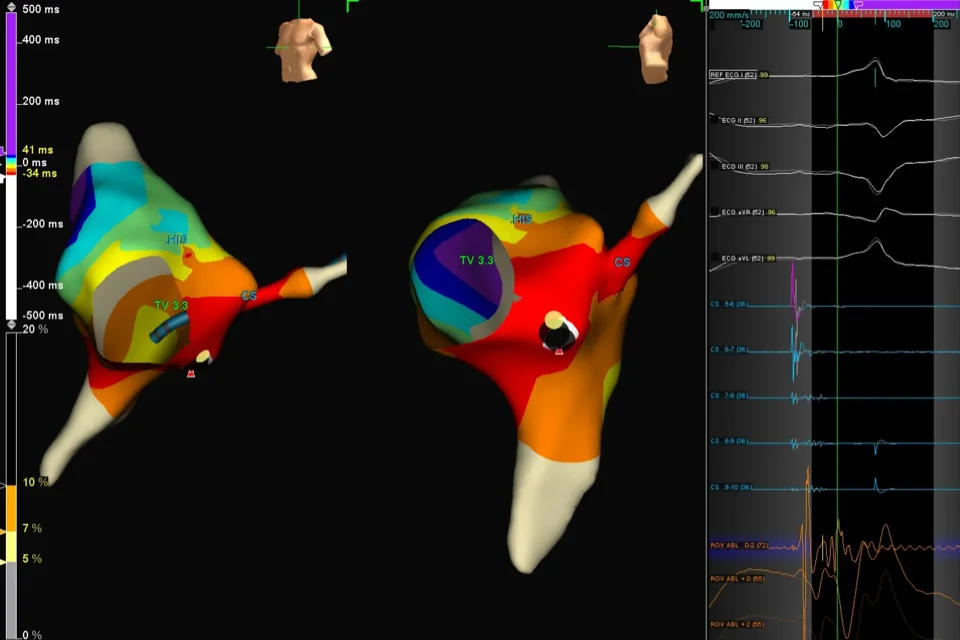

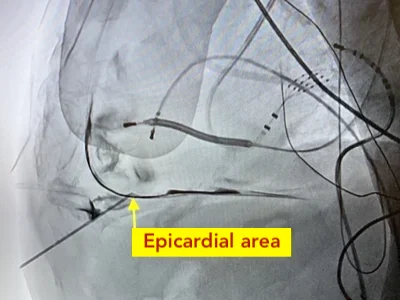

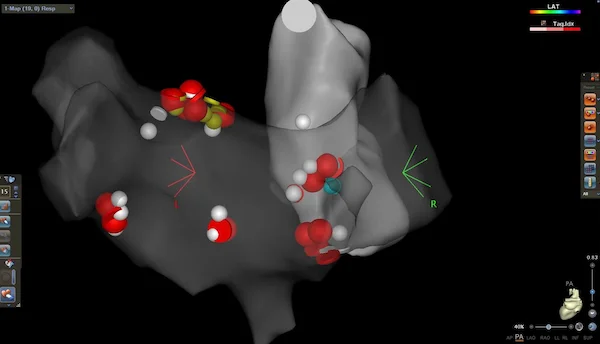

Catheters are inserted through blood vessels—most commonly in the groin—and guided to the heart. Once the source of the abnormal rhythm is identified, controlled energy is delivered through the catheter to treat the responsible area. This energy is used to interrupt the abnormal electrical signals so they can no longer trigger or maintain the arrhythmia.

Different types of energy may be used depending on the rhythm problem and treatment strategy. These include heat-based energy (radiofrequency ablation), freezing (cryoablation), and in selected cases short electrical pulses (pulsed field ablation). Your doctor will choose the most appropriate method for your specific condition.

The procedure length varies depending on the rhythm problem being treated. Some ablations are relatively short, while others may take several hours.

What Will I Feel During the Procedure?

Because sedation or anesthesia is used, most patients do not feel pain during the procedure. You may feel some pressure at the catheter insertion site.

After the procedure, mild chest discomfort, fatigue, or awareness of the heartbeat can occur. These sensations are usually temporary and improve over time.

What Happens After Cardiac Ablation?

After the procedure, you will be monitored for several hours or overnight. Most patients are able to go home the same day or the following day.

It is common to feel tired for a few days. Mild soreness or bruising at the groin site can occur. Short episodes of irregular heartbeat may happen during the early healing phase and do not necessarily mean the procedure was unsuccessful.

Recovery and Daily Life After Ablation

Most people return to normal daily activities within a few days. Heavy physical activity and strenuous exercise are usually limited for a short period, based on your doctor’s advice.

Your healthcare team will provide specific guidance on wound care, activity, driving, and return to work. Follow-up visits are important to assess rhythm control and adjust medications if needed.

Medications After Cardiac Ablation

Some patients continue rhythm medications for a period after ablation while the heart heals. In atrial fibrillation, blood-thinning medication may need to be continued depending on stroke risk, regardless of how well the rhythm is controlled.

Medication decisions after ablation are individualized and discussed during follow-up.

Risks of Cardiac Ablation

Cardiac ablation is a commonly performed and generally safe procedure, especially in experienced centers. As with any invasive procedure, risks exist. These may include bleeding or bruising at the catheter site, blood vessel injury, infection, or rhythm disturbances.

Serious complications are uncommon, and your medical team will discuss the specific risks related to your condition before the procedure.

How Successful Is Cardiac Ablation?

Cardiac ablation can successfully treat many types of heart rhythm disorders. The expected success depends on the specific rhythm problem, but for several arrhythmias, ablation offers a very high chance of long-term control or cure.

Atrial Flutter

Atrial flutter can be treated with cardiac ablation with success rates exceeding 95% in experienced centers. Because atrial flutter can increase the risk of blood clots and stroke, eliminating the abnormal circuit with ablation often allows patients to return to a normal rhythm and resume daily life without recurrent episodes.

AVNRT (Atrioventricular Nodal Reentrant Tachycardia)

AVNRT is one of the most reliably treatable rhythm disorders. Ablation has a success rate of approximately 95–98%, and in most patients, the arrhythmia does not return. After successful ablation, long-term medication is usually no longer needed.

AVRT / Wolff–Parkinson–White (WPW) Syndrome

In AVRT and WPW syndrome, an extra electrical pathway causes rapid heart rhythms. Cardiac ablation can eliminate this pathway with success rates above 95%, often providing a permanent solution and preventing future attacks.

Atrial Tachycardia

When atrial tachycardia arises from a single focal area, ablation can be highly effective. Initial success rates are commonly around 80–90%, and repeat treatment—if needed—can further improve long-term rhythm control.

Atrial Fibrillation (AF)

Cardiac ablation for atrial fibrillation is most effective in patients with paroxysmal (intermittent) AF. In this group, approximately 70–80% of patients achieve significant reduction or elimination of AF episodes after one procedure, with higher success after repeat ablation if needed. In more persistent forms of AF, ablation can still reduce symptoms and arrhythmia burden, although multiple procedures may be required.

Frequent Premature Beats (PVCs)

When premature beats are very frequent or cause symptoms or weakening of heart function, ablation can be an effective treatment. In suitable cases, success rates are commonly around 80–90%, leading to marked symptom improvement and recovery of heart function in many patients.

Ventricular Tachycardia (VT)

Ventricular tachycardia ablation is usually performed in patients with underlying heart disease. The goal is often to reduce the frequency and severity of episodes, rather than guarantee complete elimination. In experienced centers, ablation can significantly decrease VT burden and improve quality of life, especially by reducing shocks in patients with implantable defibrillators.

In Summary

Cardiac ablation is a minimally invasive procedure used to treat abnormal heart rhythms by targeting the source of the problem. It is recommended when symptoms persist, medications are ineffective, or long-term rhythm control is desired. Most patients recover quickly, experience symptom improvement, and return to normal activities within days. When carefully selected and properly performed, cardiac ablation is an effective and well-established treatment for many heart rhythm disorders.

Reference: Ablation