Supraventricular tachycardia is a arrhythmia characterized by sudden episodes of abnormally fast heartbeat that originate above the ventricles. Unlike some other rhythm problems, SVT often begins and ends abruptly, sometimes within seconds, leaving patients feeling as if a switch has been turned on and off inside their chest.

Many people with SVT are otherwise healthy and may experience long periods without symptoms. However, when an episode occurs, it can be intense and alarming, especially for those encountering it for the first time. Although SVT is usually not life-threatening, it can significantly affect quality of life and, in some cases, require medical treatment.

- How Supraventricular Tachycardia Affects the Heart

- Types of Supraventricular Tachycardia

- Symptoms of Supraventricular Tachycardia

- Why Supraventricular Tachycardia Occurs

- How Supraventricular Tachycardia Is Diagnosed

- Is Supraventricular Tachycardia Dangerous?

- Treatment Goals in Supraventricular Tachycardia

- Living With Supraventricular Tachycardia

- In Summary

How Supraventricular Tachycardia Affects the Heart

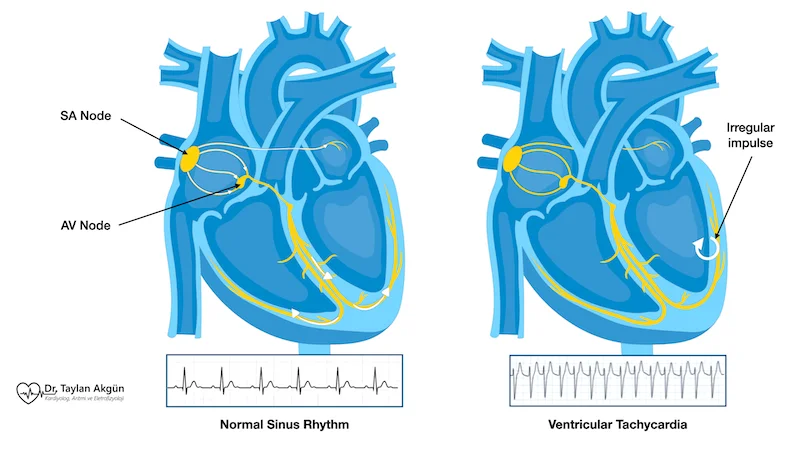

In a normal heartbeat, electrical signals follow a single, well-defined pathway that keeps the rhythm steady and controlled. In supraventricular tachycardia, an extra electrical pathway or an abnormal electrical circuit allows impulses to travel in a rapid loop.

When this loop is activated, the heart rate can suddenly increase, often reaching 150 to 250 beats per minute. Despite the rapid rate, the rhythm is usually regular, which is why SVT often feels different from irregular rhythms such as atrial fibrillation.

Because the heart is beating so fast, it has less time to fill with blood between beats. This can reduce blood flow to the body and brain, explaining many of the symptoms patients experience during an episode.

Types of Supraventricular Tachycardia

Although supraventricular tachycardia often feels similar from one person to another, it can arise from different electrical mechanisms within the heart. Understanding these types helps explain why certain treatments are highly effective and why catheter ablation can permanently resolve the problem in many patients.

The most common type of SVT is caused by a small electrical loop located near the center of the heart, close to the normal electrical connection between the upper and lower chambers. In this form, known as atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia (AVNRT), the electrical signal repeatedly circles within a tiny pathway instead of moving forward in a normal direction. AVNRT is frequently seen in otherwise healthy individuals and often responds very well to both medications and catheter ablation.

Another form of SVT involves an extra electrical pathway that directly connects the atria and ventricles. This pathway allows electrical signals to bypass the heart’s usual route and travel through a shortcut, creating a rapid looping rhythm. This mechanism is called atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia (AVRT) and is sometimes associated with conditions such as Wolff–Parkinson–White syndrome. Once the extra pathway is identified and eliminated, the rhythm disturbance can often be cured permanently.

Less commonly, SVT may originate from a single area in the atrium that begins firing rapidly on its own, overriding the heart’s natural pacemaker. This type is referred to as atrial tachycardia. In this situation, the rhythm problem is driven by an overactive focus rather than a looping circuit. Treatment depends on how frequent the episodes are and how much they interfere with daily life.

While these names may sound technical, the key message for patients is reassuring: most types of supraventricular tachycardia are caused by clearly identifiable electrical pathways or triggers. Once the exact mechanism is understood, treatment can be precisely targeted and is often highly successful.

Symptoms of Supraventricular Tachycardia

SVT symptoms often appear suddenly and may stop just as abruptly. Episodes can last from a few seconds to several hours. Some people learn to recognize the pattern over time, while others experience significant anxiety during each episode.

Before listing symptoms, it is important to note that the severity of symptoms does not always reflect the seriousness of the rhythm disturbance. Even short episodes can feel dramatic.

Common symptoms include:

- Sudden onset of rapid heartbeat

- A strong pounding sensation in the chest or neck

- Shortness of breath

- Dizziness or lightheadedness

- Chest tightness or discomfort

- Fatigue after the episode ends

In some cases, especially in younger individuals, SVT may present primarily as exercise intolerance or unexplained palpitations.

Why Supraventricular Tachycardia Occurs

SVT usually results from an electrical wiring issue present within the heart. In many patients, this wiring pattern has existed since birth, even if symptoms appear later in life. Certain triggers can activate the abnormal circuit.

Common contributing factors include:

- Extra electrical pathways in the heart

- Stress or strong emotional responses

- Caffeine or stimulant use

- Lack of sleep

- Hormonal changes

- Certain medications

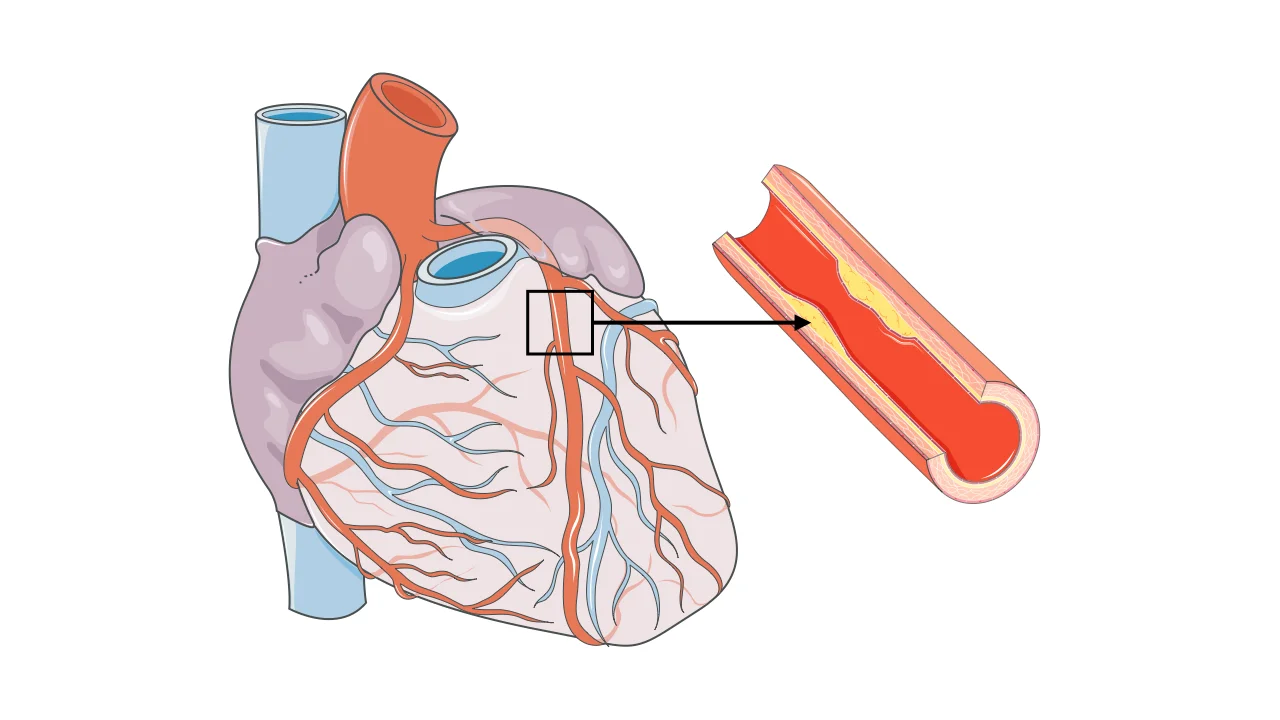

Unlike atrial fibrillation, SVT is less commonly associated with structural heart disease, especially in younger patients.

How Supraventricular Tachycardia Is Diagnosed

Diagnosis relies on documenting the fast rhythm while it is occurring. This can be challenging if episodes are brief or infrequent.

An electrocardiogram performed during an episode typically shows a fast, regular rhythm with narrow electrical complexes. If the rhythm is not captured during a clinic visit, longer-term heart rhythm monitoring may be used.

Additional tests may be performed to rule out other conditions and to better understand the heart’s electrical pathways, especially if procedural treatment is being considered.

Is Supraventricular Tachycardia Dangerous?

For most people, SVT is not dangerous in the sense of causing sudden death or permanent heart damage. However, repeated or prolonged episodes can interfere with daily life, cause significant discomfort, and lead to anxiety or avoidance of physical activity.

In rare cases, extremely rapid or frequent episodes may strain the heart, particularly in individuals with underlying heart disease.

Treatment Goals in Supraventricular Tachycardia

Treatment is aimed at stopping episodes when they occur, reducing how often they happen, and preventing recurrence when symptoms are disruptive.

Not every patient with SVT requires treatment. The decision depends on symptom severity, episode frequency, and individual preferences.

Acute Episode Management

When an episode of supraventricular tachycardia begins, the first goal is to slow down or interrupt the abnormal electrical loop that is causing the rapid heartbeat. In many cases, this can be achieved without medication.

Certain physical maneuvers activate a nerve called the vagus nerve, which plays a role in controlling heart rate. Stimulating this nerve can briefly slow electrical conduction in the heart and may stop the SVT episode altogether. These maneuvers are simple, safe, and often taught to patients once the diagnosis is confirmed.

Commonly used techniques include bearing down as if having a bowel movement, forcefully blowing into a closed mouth, or applying a cold stimulus to the face. These actions increase pressure in the chest or stimulate facial nerves, which in turn send signals to the heart that can interrupt the abnormal rhythm. While they may feel unusual, they are not dangerous when performed correctly and under medical guidance.

If these maneuvers are not effective or the episode is particularly intense, medications may be used in a medical setting. The most commonly used drug is adenosine, which is given through a vein and acts very quickly. It briefly pauses electrical conduction in the heart, allowing the normal rhythm to resume. Although the effect lasts only seconds, patients may feel a short-lived sensation of chest pressure or warmth, which passes quickly.

Other medications, such as beta blockers or calcium channel blockers like metoprolol or verapamil, may also be used depending on the situation. These drugs help slow the heart rate and stabilize the rhythm, either during an acute episode or to prevent recurrence.

The choice of treatment depends on the patient’s symptoms, heart rate, overall health, and response to initial measures. Importantly, acute episode management is focused on safety and symptom relief, while long-term treatment decisions are made after careful evaluation.

Long-Term Treatment Options

For patients with frequent or bothersome episodes, daily medications may be prescribed to reduce the likelihood of SVT occurring. These drugs help stabilize the heart’s electrical activity but do not remove the underlying circuit.

Catheter Ablation: A Curative Approach

Catheter ablation offers a definitive treatment option for many forms of supraventricular tachycardia. During this procedure, thin catheters are guided through blood vessels to the heart, where the abnormal electrical pathway is precisely identified.

Once located, the pathway is carefully eliminated using controlled energy. This interrupts the circuit responsible for SVT and prevents future episodes. In many cases, ablation provides a permanent cure, allowing patients to stop medications and return to normal activities without fear of sudden attacks.

Ablation is not performed casually; it follows careful evaluation and discussion of risks and benefits. For appropriately selected patients, success rates are high and long-term outcomes are excellent.

Living With Supraventricular Tachycardia

Many people with SVT live full, active lives. Understanding triggers, recognizing early symptoms, and knowing when to seek medical care are key aspects of management.

For those who undergo definitive treatment, SVT often becomes a closed chapter rather than a lifelong concern.

In Summary

Supraventricular tachycardia is a fast but usually organized heart rhythm that begins suddenly and often resolves just as quickly. While it is typically not dangerous, it can be disruptive and distressing. Accurate diagnosis, patient education, and individualized treatment allow most people with SVT to manage the condition effectively—or eliminate it altogether.

Reference: Supraventricular Tachycardia