Atrial flutter is a type of arrhythmia in which the upper chambers of the heart (the atria) beat very fast in a regular and organized pattern. Although the rhythm is rapid, it is more structured than atrial fibrillation, which is why atrial flutter often feels different to patients.

Atrial flutter is not usually life-threatening on its own, but it can cause significant symptoms and increases the risk of stroke. Understanding how it works—and how it differs from other arrhythmias—helps patients make informed decisions about treatment.

How Atrial Flutter Affects the Heart

In atrial flutter, a single electrical signal travels in a continuous loop within the atrium. Instead of stopping after each beat, the signal circulates rapidly, causing the atria to contract at very high rates.

Because the atrioventricular (AV) node cannot conduct every signal to the ventricles, only some of these rapid atrial beats are transmitted. This results in a fast but often regular pulse, commonly around 120–150 beats per minute.

This organized electrical loop is the key feature that distinguishes atrial flutter from atrial fibrillation.

Symptoms of Atrial Flutter

The symptoms of atrial flutter depend on how fast the ventricles are beating and how long the rhythm persists. Some people feel symptoms immediately, while others may tolerate the rhythm for some time.

Common symptoms include:

- Rapid or pounding heartbeat

- Palpitations

- Shortness of breath

- Fatigue or reduced exercise tolerance

- Dizziness or lightheadedness

In some cases, atrial flutter is discovered incidentally during routine testing, even when symptoms are mild or absent.

Why Atrial Flutter Occurs

Atrial flutter often develops in the presence of underlying heart conditions, but it can also occur in otherwise healthy individuals.

Common contributing factors include high blood pressure, heart valve disease, prior heart surgery, cardiomyopathy, and chronic lung disease. In some patients, atrial flutter appears after episodes of atrial fibrillation or following catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation.

Identifying contributing conditions is important because treating them can reduce recurrence and improve outcomes.

Types of Atrial Flutter

Atrial flutter is classified based on the location and direction of the electrical loop.

- Typical atrial flutter follows a well-defined circuit in the right atrium. This form is the most common and is highly amenable to catheter ablation.

- Atypical atrial flutter involves less predictable circuits, often occurring after heart surgery or prior ablation procedures. These forms may be more complex to treat and require advanced mapping techniques.

Atrial Flutter vs Atrial Fibrillation

Although atrial flutter and atrial fibrillation are related, they are not the same condition.

Atrial flutter produces a fast but regular rhythm, while atrial fibrillation causes a chaotic and irregular rhythm. Some patients experience both conditions at different times. Importantly, both carry a risk of stroke and often require similar approaches to anticoagulation.

Distinguishing between the two helps guide rhythm control strategies but does not eliminate the need for stroke prevention.

How Atrial Flutter Is Diagnosed

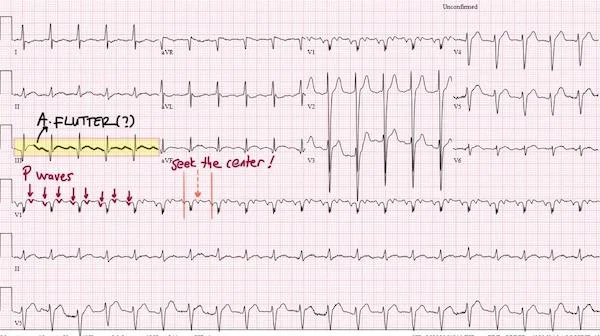

Atrial flutter is usually diagnosed with an electrocardiogram, which shows a characteristic repeating pattern often described as a “sawtooth” appearance. Because episodes can come and go, rhythm monitoring may be needed if symptoms are intermittent.

Additional testing may be performed to assess heart structure, identify contributing conditions, and guide treatment decisions.

Treatment Options for Atrial Flutter

Treatment focuses on symptom relief, rhythm control, and stroke prevention.

Medications may be used to slow the heart rate or help maintain normal rhythm. In many cases, electrical cardioversion is used to restore normal rhythm, particularly when symptoms are significant.

Catheter ablation plays a central role in the management of typical atrial flutter. By interrupting the electrical loop responsible for the rhythm, ablation offers very high success rates and is often considered a definitive treatment.

For typical atrial flutter, catheter ablation is associated with very high success rates, exceeding 95% in experienced centers. Recurrence after successful ablation is uncommon, and in most patients the rhythm problem does not return after a single procedure.

Because of its high effectiveness, relatively low complication risk, and the potential to avoid long-term medication use, ablation is often recommended for patients with recurrent or symptomatic atrial flutter. In many cases, it may also be considered even after one or two episodes, particularly when symptoms are significant or poorly tolerated.

Living With Atrial Flutter

A diagnosis of atrial flutter can be unsettling, especially when episodes are frequent or symptomatic. With modern treatment strategies—particularly catheter ablation—most patients achieve excellent symptom control and quality of life.

Regular follow-up is important, as some patients may later develop atrial fibrillation even after successful flutter treatment.

In Summary

Atrial flutter is a fast but organized heart rhythm originating in the atria. While it is often less chaotic than atrial fibrillation, it can cause significant symptoms and carries a risk of stroke. Accurate diagnosis and individualized treatment—including catheter ablation in many cases—allow most patients to manage atrial flutter safely and effectively.

Reference: Atrial Flutter