Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome is a heart rhythm condition that you are born with. It happens because your heart has an extra electrical connection, which can sometimes cause episodes of very fast heartbeat.

Most of the time, you may feel completely well. However, some people experience sudden attacks of rapid heartbeats that can feel alarming, especially when they start without warning.

It is important to know that WPW is not caused by heart damage, stress, or lifestyle habits. It is simply a variation in the heart’s electrical wiring that develops before birth.

How WPW Affects Your Heart

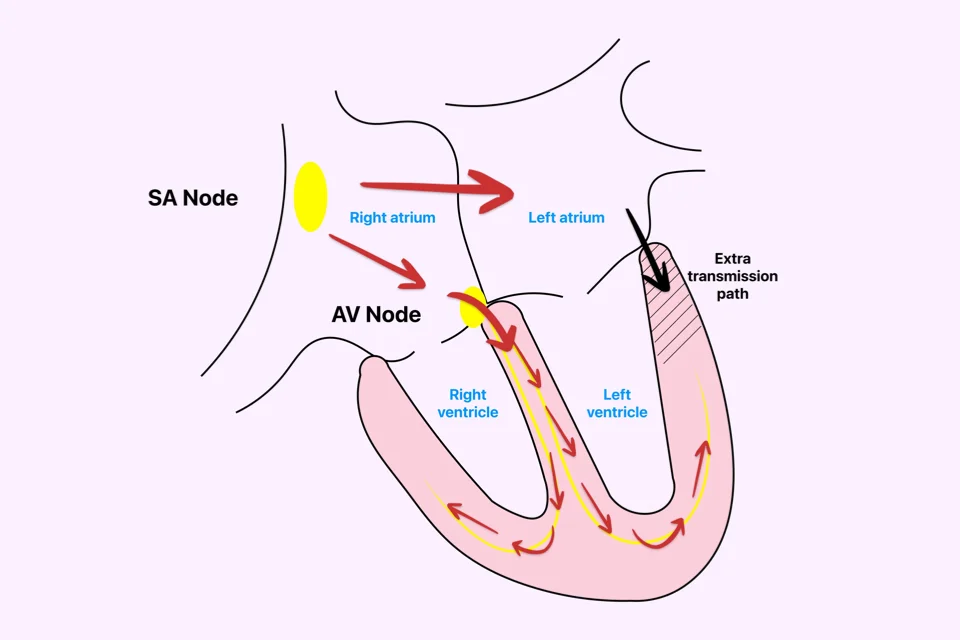

In a normal heart, electrical signals follow a single, controlled pathway. This ensures that each heartbeat happens in a smooth and coordinated way.

If you have WPW, an extra electrical pathway allows signals to travel along a shortcut. Under certain conditions, this can cause the electrical impulses to circulate rapidly, leading to a sudden and very fast heartbeat.

This is why WPW episodes often:

- Start suddenly

- Stop suddenly

- Cause the heart rate to jump very quickly

Symptoms of WPW Syndrome

Symptoms vary from person to person. Some people never notice any symptoms, and WPW is found by chance during a routine ECG test. Others may experience noticeable and repeated episodes.

It is important to understand that even mild symptoms should be evaluated, as symptom severity does not always reflect risk.

Common symptoms include:

- Sudden episodes of fast heartbeat

- Strong or pounding palpitations

- Shortness of breath during attacks

- Dizziness or lightheadedness

- Chest discomfort

- Tiredness after the episode ends

In rare cases, fainting may occur, especially during very rapid rhythms.

WPW and SVT

WPW is closely linked to certain types of fast heart rhythm attacks called supraventricular tachycardia (SVT).

Because of the extra pathway, electrical signals can loop between the upper and lower chambers of your heart, creating a rapid and organized rhythm. These episodes are usually not life-threatening, but they can be uncomfortable, frightening, and unpredictable.

Understanding this connection helps explain why WPW is often discussed together with SVT.

Why WPW Is Taken Seriously

Most people with WPW live normal, active lives and do not experience serious complications. However, in a small number of individuals, the extra electrical pathway can carry signals very rapidly.

If certain irregular heart rhythms occur (especially atrial fibrillation) these fast signals may pass directly to the lower chambers of the heart. This can cause the heart to beat dangerously fast, a situation known as rapid ventricular response.

Although this is uncommon, it is the main reason WPW is evaluated carefully and monitored closely. Early assessment allows doctors to identify higher-risk pathways and recommend treatment when needed, helping prevent potentially serious rhythm problems.

How WPW Is Diagnosed

WPW is usually diagnosed with an electrocardiogram (ECG). Even if you feel well, the ECG may show specific patterns that indicate the presence of an extra pathway.

If you have symptoms or if further assessment is needed, your doctor may recommend:

- Heart rhythm monitoring

- Exercise testing

- Advanced electrical studies

These tests help determine how your extra pathway behaves and whether treatment is needed.

Treatment Options for WPW Syndrome

Not everyone with WPW needs treatment. Your care plan depends on:

- Your symptoms

- Test results

- How your extra pathway behaves

- Your overall risk level

Some people benefit from medications that reduce the likelihood of fast heart rhythm episodes.

If you have frequent symptoms or higher-risk features, catheter ablation is often recommended. During this procedure:

- Thin flexible tubes are guided into your heart

- The extra electrical pathway is carefully located

- Controlled energy is used to eliminate it

Once the pathway is removed, WPW is effectively cured, and normal electrical conduction is restored.

In experienced centers, catheter ablation has success rates above 95% and is considered a safe and definitive treatment.

Living With WPW Syndrome

Being told you have WPW can feel worrying, especially if it is discovered unexpectedly. The good news is that most people live full, active, and normal lives.

Learning to recognize your symptoms, understanding your condition, and knowing when to seek medical advice can greatly reduce anxiety and help you stay confident in daily life.

With proper follow-up and individualized care, long-term outlook is excellent.

Reference: WPW Syndrome