Heart block, also called atrioventricular (AV) block, is a condition in which the electrical signals that control your heartbeat slow down or fail to reach the lower chambers of your heart properly. As a result, your heart may beat too slowly, irregularly, or less efficiently.

Heart block can range from mild and harmless to serious and potentially life-threatening, depending on how much the electrical signal is delayed or blocked.

How Your Heart’s Electrical System Works

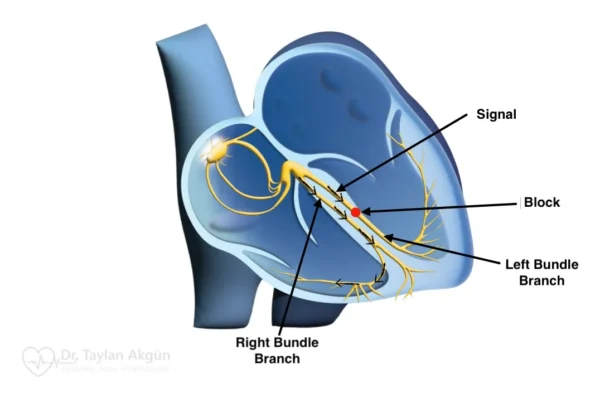

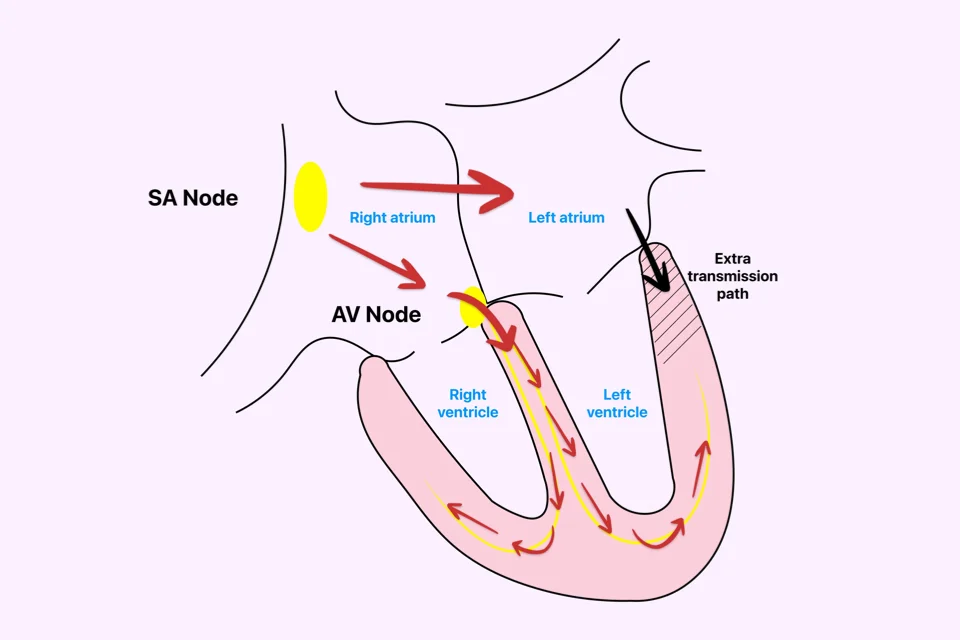

Each heartbeat starts with an electrical signal produced by your heart’s natural pacemaker. This signal spreads through the upper chambers of your heart (atria), making them contract and push blood into the lower chambers (ventricles).

The signal then passes through a small electrical gateway between the atria and ventricles. This short delay is important because it allows the ventricles time to fill with blood before they contract and pump blood to the rest of your body.

Heart block happens when this electrical signal travels too slowly or does not pass through properly.

What Happens in Heart Block

If you have heart block, electrical signals may reach the ventricles late, occasionally, or not at all. This can cause your heart to beat too slowly.

When your heart rate is too slow, your body may not receive enough blood and oxygen — especially during activity. This can lead to symptoms such as fatigue, dizziness, and fainting.

Symptoms of Heart Block

Many people with mild heart block feel completely well and have no symptoms. More advanced forms, however, can cause noticeable and sometimes worrying symptoms.

It is important to know that symptoms do not always match the severity of heart block. Some people adapt slowly, while others develop symptoms suddenly.

Common symptoms include:

- Feeling tired or low in energy

- Dizziness or lightheadedness

- Shortness of breath during activity

- Reduced ability to exercise

- Near-fainting or fainting

- A slow or irregular pulse

In severe cases, heart block can cause sudden loss of consciousness, which requires urgent medical attention.

Types of Heart Block

Heart block is classified based on how much the electrical signal is delayed or blocked. This helps guide treatment decisions.

First-Degree AV Block

In first-degree heart block, all electrical signals reach the ventricles, but they travel more slowly than normal.

This type is often discovered by chance during an ECG test and usually causes no symptoms. In most cases, it does not require treatment and only needs observation.

Second-Degree AV Block

In second-degree heart block, some electrical signals fail to reach the ventricles, causing occasional missed heartbeats.

There are two main types:

- Type I: The electrical delay gradually increases until a beat is skipped. This form is often mild and may not need treatment unless symptoms occur.

- Type II: Some signals suddenly fail to pass through without warning. This type is more serious and can progress to complete heart block.

Third-Degree (Complete) AV Block

In complete heart block, none of the electrical signals from the atria reach the ventricles. The ventricles then produce their own slow backup rhythm, which is usually not enough to meet your body’s needs.

This form almost always causes symptoms and requires urgent treatment, most often with a pacemaker.

Why Heart Block Develops

Heart block can develop for many reasons, including:

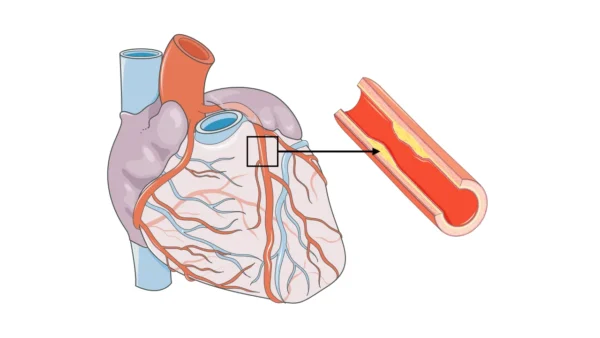

- Natural aging and gradual wear of the heart’s electrical system

- Heart attack or heart surgery

- Inflammation of the heart

- Certain medications that slow electrical conduction

- Rarely, electrical pathway abnormalities present from birth

Finding the underlying cause is important, as some types of heart block can improve once the cause is treated.

How Heart Block Is Diagnosed

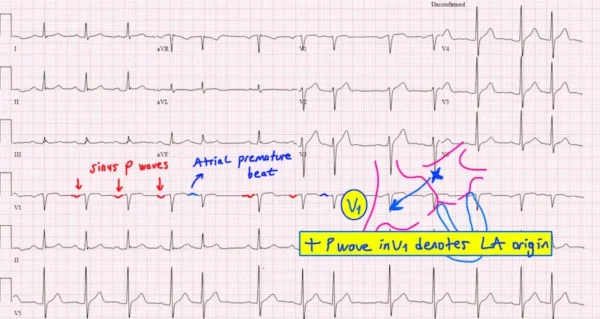

Heart block is usually diagnosed using an electrocardiogram (ECG), which shows how electrical signals travel through your heart.

If heart block occurs only occasionally, longer-term heart rhythm monitoring may be recommended. Additional tests may be used to assess heart structure, detect reversible causes, and evaluate the risk of progression.

Treatment Options for Heart Block

Treatment depends on:

- The type of heart block

- Whether you have symptoms

- The underlying cause

Mild forms may only require regular follow-up and observation. If medications are contributing, adjusting or stopping them may restore normal conduction.

If heart block is more advanced or causes symptoms such as dizziness or fainting, a pacemaker is often recommended.

A pacemaker is a small device placed under your skin that helps regulate your heartbeat by providing reliable electrical signals. It ensures your heart beats at a safe and steady rate.

Pacemaker treatment does not cure the electrical condition itself, but it effectively restores a stable heart rhythm and greatly improves quality of life.

Living With Heart Block

Being diagnosed with heart block can feel worrying, especially if symptoms are present. With proper treatment and regular follow-up, however, most people lead full, active, and independent lives.

Ongoing medical care, awareness of symptoms, and regular check-ups play a key role in long-term health and safety.

Reference: Atrioventricular Block