Heart failure doesn’t mean your heart has stopped working or is about to stop. Instead, it means your heart can’t pump blood efficiently enough to meet your body’s needs. This weakened pumping ability develops gradually, often over years, causing symptoms that worsen slowly or appear suddenly during times of stress. You might feel constantly exhausted, become breathless with minimal activity, or notice swelling in your legs and feet.

Overview

Heart failure is a chronic condition where your heart muscle becomes too weak or stiff to pump blood effectively throughout your body. Your organs and tissues don’t receive adequate oxygen and nutrients, and fluid backs up in your lungs and other parts of your body.

Your heart has four chambers—two upper chambers called atria and two lower chambers called ventricles. The left ventricle is the main pumping chamber, responsible for sending oxygen-rich blood to your entire body. When it weakens or stiffens, heart failure develops.

There are two main types based on how the heart fails. Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, previously called systolic heart failure, occurs when the left ventricle becomes weak and doesn’t contract forcefully enough. Ejection fraction—the percentage of blood pumped out with each beat—drops below 40%, compared to the normal 50-70%. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, previously called diastolic heart failure, occurs when the left ventricle becomes stiff and can’t relax properly between beats. It fills inadequately even though it squeezes normally. Ejection fraction remains 50% or higher, but the heart still can’t pump enough blood.

Heart failure is classified by severity using the New York Heart Association system. Class I means you have heart failure but no symptoms with normal activity. Class II means you’re comfortable at rest but ordinary activity causes fatigue or shortness of breath. Class III means you’re comfortable at rest but less than ordinary activity causes symptoms. Class IV means you’re symptomatic even at rest and any activity worsens symptoms.

Causes

Heart failure develops when conditions damage your heart muscle or force it to work too hard for too long.

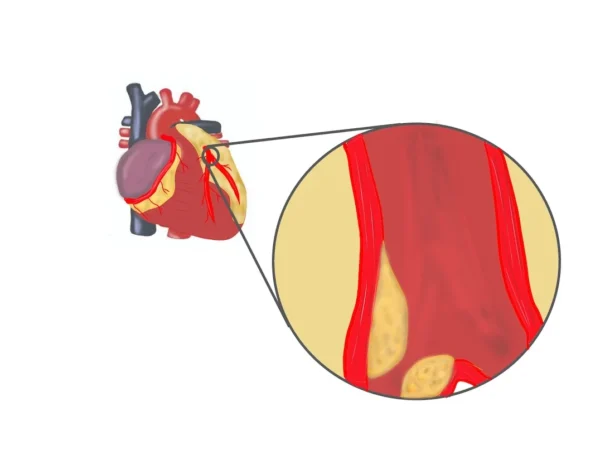

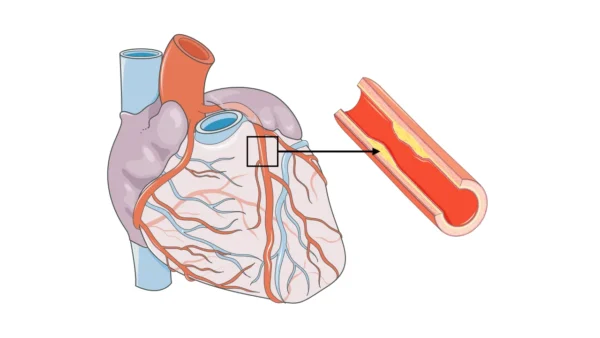

- Coronary artery disease is the most common cause. Blocked arteries reduce blood flow to heart muscle, weakening it over time. Heart attacks cause sudden damage by killing sections of heart muscle, leaving scar tissue that can’t contract. Multiple small heart attacks or one large one can both lead to heart failure.

- High blood pressure forces your heart to work harder to pump blood against increased resistance. Over years or decades, this constant extra effort causes the heart muscle to thicken and eventually weaken. Uncontrolled hypertension is a major preventable cause of heart failure.

- Cardiomyopathy refers to diseases of the heart muscle itself. Dilated cardiomyopathy causes the heart to enlarge and weaken. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy involves abnormal thickening of heart muscle. Restrictive cardiomyopathy makes the heart stiff. These conditions can be inherited or develop from various causes including infections, alcohol, chemotherapy drugs, or unknown reasons.

- Heart valve disease forces the heart to work harder. Leaking valves allow blood to flow backward, requiring the heart to pump the same blood multiple times. Narrowed valves make the heart work harder to push blood through. Over time, this extra workload weakens the muscle.

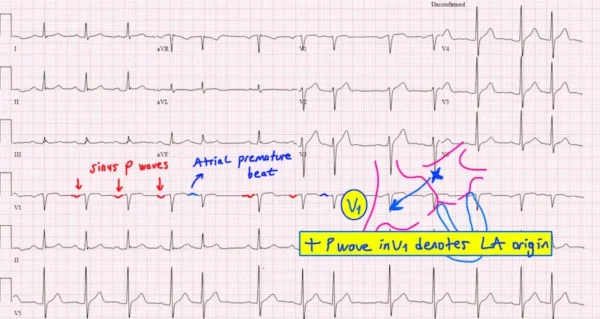

- Arrhythmias, particularly chronic rapid rhythms like atrial fibrillation, can weaken the heart if rates aren’t controlled. Very slow heart rates sometimes cause heart failure by inadequate blood flow.

- Myocarditis, or inflammation of the heart muscle from viral infections or autoimmune diseases, can damage heart tissue and lead to heart failure.

- Diabetes increases heart failure risk through multiple mechanisms—contributing to coronary disease, directly affecting heart muscle, and often coexisting with high blood pressure and obesity.

- Obesity stresses the heart by increasing the volume of blood that must be pumped and contributing to high blood pressure, diabetes, and sleep apnea.

- Sleep apnea, where breathing repeatedly stops during sleep, stresses the heart through oxygen drops and surges of stress hormones.

- Excessive alcohol consumption over years can directly damage heart muscle, causing alcoholic cardiomyopathy.

- Chemotherapy drugs, particularly certain ones used for cancer treatment, can damage heart muscle. This risk is weighed against cancer treatment benefits.

- Congenital heart defects present from birth sometimes lead to heart failure as the abnormal heart structure struggles over years.

- Aging itself contributes—heart muscle naturally stiffens with age, increasing risk for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction.

Symptoms

Heart failure symptoms develop gradually as your heart’s pumping ability declines, though sometimes they appear suddenly.

- Shortness of breath is the hallmark symptom. Initially, you notice it only during exertion—climbing stairs, walking uphill, or exercising. As heart failure worsens, less and less activity triggers breathlessness. Eventually, you might feel short of breath at rest or when lying flat. Many people need to sleep propped up on multiple pillows or in a recliner because lying flat causes fluid to redistribute to the lungs, making breathing difficult. Waking at night gasping for air, called paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, is particularly characteristic.

- Fatigue and weakness are profound and persistent. You feel exhausted with minimal activity. Simple tasks like showering, getting dressed, or making a meal become exhausting. This isn’t just being tired—it’s a deep, overwhelming fatigue that rest doesn’t relieve.

- Swelling, called edema, typically starts in the feet and ankles, particularly noticeable at the end of the day. As heart failure worsens, swelling progresses up the legs to the calves, knees, and thighs. Some people develop swelling in the abdomen. Weight gain from fluid retention can be dramatic—several pounds in just days. Your shoes might suddenly feel tight, rings won’t fit, or pants become snug around the waist.

- Persistent cough or wheezing occurs as fluid accumulates in the lungs. You might cough up white or pink-tinged mucus. This is often worse at night or when lying down.

- Rapid or irregular heartbeat develops as your heart tries to compensate for weak pumping by beating faster. You might feel palpitations or notice your heart racing.

- Reduced appetite and nausea result from fluid accumulation in your digestive system, making you feel full even after eating small amounts.

- Confusion or impaired thinking can occur in severe heart failure when your brain doesn’t receive adequate blood flow. Older adults might become confused or disoriented.

- Exercise intolerance is a sensitive early sign. Activities you once did easily become difficult or impossible. You might notice you can’t walk as far or as fast as before.

- Some people have few symptoms despite significant heart failure, particularly with preserved ejection fraction where symptoms develop more gradually.

Diagnosis

Diagnosing heart failure involves confirming the condition, determining its cause, and assessing severity.

- Your medical history and symptom description provide crucial clues. Your doctor asks about shortness of breath patterns, when symptoms occur, what worsens or improves them, and whether you have risk factors like high blood pressure, diabetes, or coronary disease.

- Physical examination reveals signs including swelling in legs or abdomen, fluid in lungs heard through a stethoscope, elevated neck veins indicating increased pressure in the heart, rapid heartbeat, and sometimes abnormal heart sounds.

- Blood tests check several markers. BNP or NT-proBNP are hormones released when the heart is stressed. Elevated levels support heart failure diagnosis and help assess severity. Other tests check kidney function, electrolytes, blood counts, thyroid function, and sometimes markers of heart muscle damage.

- Chest X-ray shows heart size and whether fluid has accumulated in the lungs. An enlarged heart or pulmonary congestion visible on X-ray supports heart failure diagnosis.

- Electrocardiogram records your heart’s electrical activity, identifying arrhythmias, evidence of previous heart attacks, or other abnormalities that contribute to or result from heart failure.

- Echocardiography is the most important test for diagnosing and characterizing heart failure. This ultrasound examination shows how well your heart pumps, measures ejection fraction, evaluates valve function, assesses chamber sizes, and identifies regional wall motion abnormalities suggesting previous heart attacks. This test distinguishes reduced from preserved ejection fraction heart failure and identifies underlying causes.

- Stress testing evaluates how your heart responds to exertion. This might involve exercise on a treadmill or medications that simulate exercise effects. Stress testing helps identify coronary artery disease as a cause.

- Cardiac catheterization might be performed to evaluate coronary arteries, particularly if coronary disease is suspected. This invasive test threads catheters through blood vessels to your heart, allowing direct visualization of arteries and measurement of pressures inside heart chambers.

- Cardiac MRI provides detailed images of heart structure and function, identifies scar tissue from previous heart attacks, and evaluates specific cardiomyopathies.

- Sometimes heart muscle biopsy is performed if specific causes like infiltrative diseases are suspected. A small tissue sample is removed through a catheter for microscopic examination.

Treatment

Heart failure treatment aims to improve symptoms, slow progression, and prolong life through multiple approaches used in combination.

- Medications form the cornerstone of treatment. ACE inhibitors or ARBs help the heart pump more efficiently, reduce blood pressure, and improve survival. Beta-blockers slow heart rate, reduce blood pressure, and have been proven to improve survival significantly. These medications might make you feel worse initially before benefits appear over weeks to months. Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists like spironolactone improve survival, particularly in more severe heart failure. SGLT2 inhibitors, originally diabetes drugs, dramatically reduce heart failure hospitalizations and improve outcomes. Diuretics, or water pills, relieve fluid retention and breathlessness by increasing urine output.

- Additional medications are added based on your specific situation. Digoxin helps control heart rate and can improve symptoms. Hydralazine and nitrates benefit some people, particularly African Americans. Ivabradine slows heart rate in specific situations.

- The medication regimen is often complex, requiring multiple pills several times daily. Taking medications exactly as prescribed is crucial—these aren’t just symptom relievers but life-prolonging treatments. Never stop heart failure medications without consulting your doctor, as sudden discontinuation can trigger dangerous deterioration.

- Devices help many people with heart failure. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillators prevent sudden death from dangerous heart rhythms, recommended for people with severely reduced ejection fraction. Cardiac resynchronization therapy uses a special pacemaker with three leads to coordinate heart contractions, improving pumping efficiency in people with electrical conduction delays. This dramatically improves symptoms and survival in appropriate candidates.

- For advanced heart failure not responding to medications and devices, mechanical circulatory support devices called LVADs (left ventricular assist devices) can be implanted. These pumps help the heart circulate blood, either as a bridge to transplant or as permanent therapy.

- Heart transplantation remains an effective treatment in appropriate candidates.

- Treating underlying causes is essential. Coronary artery bypass surgery or stenting can restore blood flow if blockages are causing heart failure. Valve repair or replacement corrects valvular disease. Controlling high blood pressure, managing diabetes, and addressing sleep apnea all improve heart failure control.

- Regular monitoring through follow-up appointments allows early detection of worsening and medication adjustments before serious decompensation occurs.

What Happens If Left Untreated

Untreated heart failure progressively worsens, leading to increasing disability and shortened lifespan.

- Symptoms steadily deteriorate. Activities that were once possible become impossible. You become increasingly breathless, fatigued, and limited. Eventually, even rest provides no relief from shortness of breath.

- Hospitalizations become frequent as acute decompensation occurs repeatedly. Each hospitalization indicates worsening disease and increases risk of subsequent hospitalizations.

- Kidney function deteriorates because inadequate cardiac output reduces blood flow to kidneys. This worsens fluid retention and creates a vicious cycle.

- Liver damage can occur from chronic congestion as blood backs up from the weakened heart.

- Heart rhythm problems become more common and severe as the heart muscle deteriorates and stretches.

- Blood clots can form in dilated, poorly contracting heart chambers, potentially traveling to the brain and causing stroke.

- Cardiac cachexia, a state of severe weight loss and muscle wasting, develops in advanced heart failure. The body consumes its own tissues for energy as circulation inadequacy prevents adequate nutrient delivery.

- Quality of life becomes severely impaired. Simple activities like bathing, dressing, or walking across a room become impossible. Many people become bedbound, dependent on others for all care.

- Sudden cardiac death from dangerous heart rhythms can occur, particularly in people with severely reduced ejection fraction who don’t have ICDs.

- Life expectancy without treatment is significantly shortened. The five-year survival rate for untreated severe heart failure is worse than many cancers.

What to Watch For

If you have heart failure, recognizing worsening symptoms allows early intervention before serious decompensation.

- Rapid weight gain is one of the most important warning signs. Gaining three or more pounds in one day or five or more pounds in a week indicates fluid accumulation. Weigh yourself daily at the same time, typically after waking and using the bathroom, in similar clothing.

- Increasing shortness of breath, particularly if it comes on suddenly or worsens over days, requires prompt medical attention. Needing more pillows to sleep or sleeping in a chair when you previously slept flat signals worsening.

- Worsening swelling in your legs, ankles, or abdomen means fluid retention is increasing. New or worsening abdominal bloating or discomfort suggests fluid accumulation.

- Persistent cough, particularly if productive of frothy or pink-tinged sputum, indicates pulmonary congestion.

- Increasing fatigue beyond your baseline, particularly if it comes on suddenly, might signal worsening heart failure.

- Reduced urine output despite adequate fluid intake suggests kidneys aren’t getting adequate blood flow.

- Loss of appetite or nausea can indicate worsening heart failure affecting your digestive system.

- Confusion or difficulty concentrating might mean your brain isn’t receiving adequate blood flow.

- Chest pain or palpitations could indicate heart rhythm problems or worsening coronary disease.

- Your doctor will teach you action plans for these symptoms. Some warrant same-day appointments, others require emergency evaluation. Never hesitate to contact your healthcare team when symptoms worsen—early intervention prevents hospitalizations.

Potential Risks and Complications

Heart failure itself and its treatments carry various risks.

- The condition progressively worsens over time despite treatment in many people, though the rate varies enormously between individuals.

- Sudden cardiac death from dangerous heart rhythms is a major risk in people with severely reduced ejection fraction, though ICDs dramatically reduce this risk.

- Stroke risk increases, particularly if atrial fibrillation develops. Blood thinners might be necessary.

- Kidney damage from reduced blood flow can progress to kidney failure requiring dialysis.

- Medication side effects vary by drug. ACE inhibitors can cause cough and affect kidney function. Beta-blockers might cause fatigue or low blood pressure. Diuretics can cause electrolyte imbalances and dehydration.

- Device complications for ICDs and CRT devices include infection, lead malfunction, inappropriate shocks, and the need for eventual replacement as batteries deplete.

- Depression and anxiety are common with heart failure, understandably given the chronic symptoms and life changes required. Mental health support is an important part of comprehensive care.

- Hospitalizations themselves carry risks including infections, blood clots, and deconditioning.

Diet and Lifestyle

Lifestyle modifications are as important as medications for managing heart failure.

- Limit sodium intake to less than 2,000-3,000 mg daily, sometimes less if your doctor recommends. Excess salt causes fluid retention, worsening symptoms. Read food labels carefully, avoid adding salt to food, and minimize processed foods, canned soups, deli meats, and restaurant meals, which are typically very high in sodium.

- Fluid restriction might be necessary if you retain fluid easily. Your doctor provides specific guidance, often limiting fluids to 1.5-2 liters daily in advanced heart failure.

- Maintain healthy weight. Obesity worsens heart failure, so weight loss is important for overweight individuals. However, unintentional weight loss suggests worsening heart failure or cardiac cachexia and requires immediate medical attention.

- Exercise regularly within your capabilities. Cardiac rehabilitation programs designed for heart failure patients safely increase exercise tolerance. Walking is excellent. Start slowly and gradually increase duration and intensity as tolerated. Exercise improves symptoms, quality of life, and potentially survival. Never start vigorous exercise without discussing with your doctor.

- Stop smoking immediately. Smoking damages blood vessels, worsens heart disease, and significantly increases heart failure mortality.

- Limit or eliminate alcohol. Excessive drinking directly damages heart muscle. Even moderate drinking might worsen heart failure. Discuss safe alcohol limits with your doctor.

- Get adequate sleep. Fatigue is already problematic in heart failure—poor sleep worsens it. Treat sleep apnea if present.

- Stay up to date with vaccinations, particularly flu and pneumonia vaccines. Infections stress your heart and can trigger acute decompensation.

- Monitor your weight daily and keep a log. This helps detect fluid retention early.

- Take all medications exactly as prescribed, even when feeling well. These medications work even if you don’t feel immediate effects.

Prevention

While not all heart failure is preventable, addressing risk factors dramatically reduces your chances of developing this condition.

- Control high blood pressure through medication if needed, along with diet, exercise, and stress management. This is perhaps the most important modifiable risk factor.

- Manage diabetes carefully. Good blood sugar control reduces cardiovascular complications including heart failure.

- Maintain healthy cholesterol levels through diet, exercise, and medications if necessary. This prevents coronary artery disease that leads to heart failure.

- Don’t smoke. If you do, quit. Smoking damages blood vessels and heart muscle.

- Maintain healthy weight. Obesity significantly increases heart failure risk through multiple mechanisms.

- Exercise regularly. Physical activity strengthens your cardiovascular system and reduces heart failure risk.

- Limit alcohol consumption. Heavy drinking causes direct heart muscle damage.

- Treat sleep apnea if present. This condition stresses the heart and promotes hypertension.

- Manage stress through healthy coping mechanisms. Chronic stress affects cardiovascular health.

- Regular medical checkups allow early detection and treatment of conditions that lead to heart failure.

- If you have coronary artery disease, follow your treatment plan carefully. Preventing or minimizing heart attacks prevents subsequent heart failure.

Key Points

- Heart failure is a chronic condition where your heart can’t pump blood effectively enough to meet your body’s needs. It doesn’t mean your heart has stopped or is about to stop—it means the pumping function is impaired.

- Two main types exist based on ejection fraction. Reduced ejection fraction means weak pumping, while preserved ejection fraction means stiff heart muscle that can’t relax properly. Treatment approaches differ between types.

- Shortness of breath, fatigue, and swelling are the cardinal symptoms. These typically develop gradually but can appear suddenly. Worsening symptoms require prompt medical attention.

- Treatment has advanced dramatically. Combination therapy with multiple medications, appropriate devices, and lifestyle modifications can significantly improve symptoms, reduce hospitalizations, and prolong life.

- Daily weight monitoring is crucial. Sudden weight gain from fluid retention is one of the earliest signs of worsening heart failure and allows intervention before serious decompensation.

- Medications must be taken exactly as prescribed even when you feel well. These aren’t just symptom relievers—they prevent progression and improve survival.

- Heart failure is manageable, not a death sentence. Many people live for years or even decades with good quality of life through proper treatment and self-management.

- Following sodium and fluid restrictions, taking medications consistently, exercising appropriately, and maintaining close contact with your healthcare team are essential for optimal outcomes.

- Work closely with a cardiologist experienced in heart failure management. These specialists understand the complex medication regimens, device therapies, and when advanced treatments like transplant evaluation might be appropriate. Heart failure management requires ongoing adjustment and optimization—what works initially might need modification as your condition evolves. The goal is always maximizing both longevity and quality of life, allowing you to remain as active and independent as possible for as long as possible.

Reference: Heart Failure