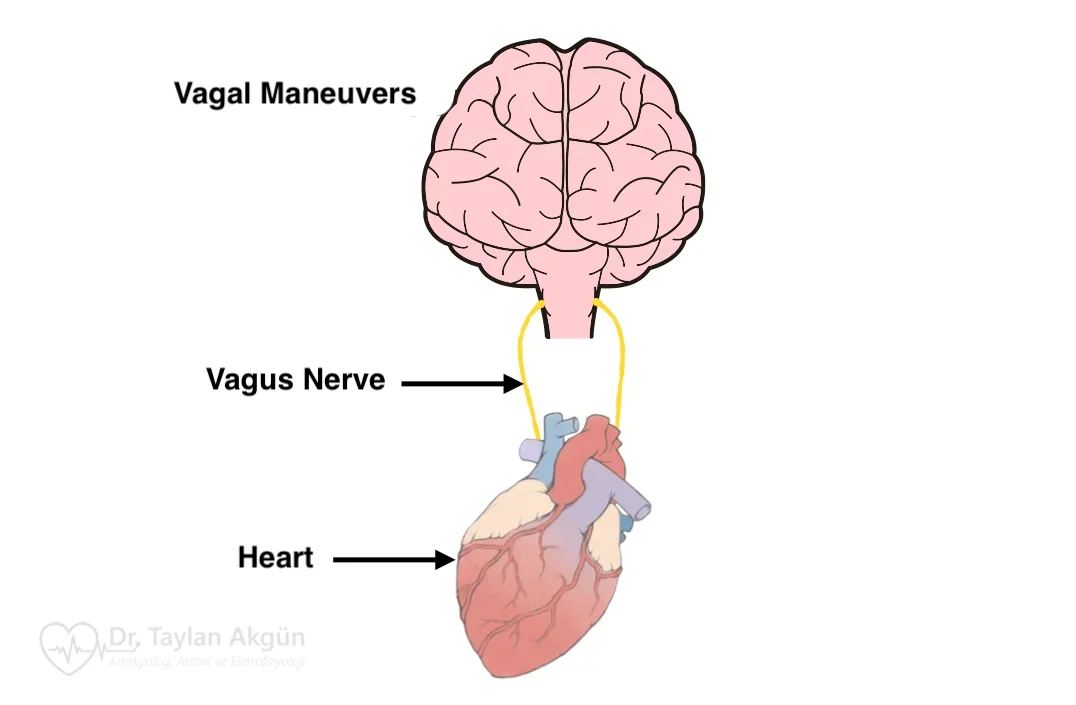

Vagal maneuvers are simple, non-invasive techniques used to slow the heart rate or stop certain types of sudden rapid heart rhythms, most commonly supraventricular tachycardia (SVT). They work by stimulating the vagus nerve, which plays a key role in controlling heart rate and electrical conduction within the heart.

These maneuvers are often recommended as a first-line response when a rapid heartbeat begins suddenly and the person is otherwise stable. When performed correctly, they can sometimes restore normal rhythm without the need for medication or emergency treatment.

How Vagal Maneuvers Work

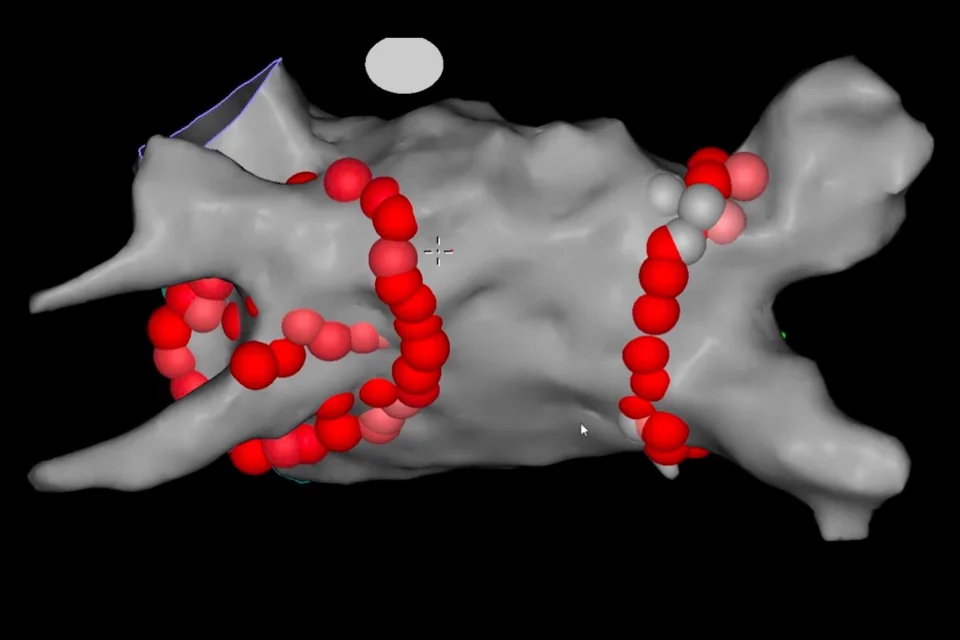

The vagus nerve helps regulate electrical signals passing through the atrioventricular (AV) node, a critical relay point between the upper and lower chambers of the heart. When the vagus nerve is stimulated, conduction through the AV node temporarily slows.

For certain rhythm disorders that depend on this pathway—particularly re-entrant supraventricular arrhythmias—this brief slowing can interrupt the abnormal electrical circuit and stop the rapid rhythm.

When Vagal Maneuvers Are Useful

Vagal maneuvers are most effective for heart rhythms that start and stop suddenly and have been previously identified as vagally responsive. They are typically used at the onset of symptoms such as a sudden racing heartbeat or pounding in the chest.

They are not appropriate for all arrhythmias and should only be used if a healthcare professional has confirmed that your rhythm disorder is suitable for this approach.

Common Vagal Maneuvers Explained in Detail

The modified Valsalva maneuver is the most effective and commonly recommended technique. It is designed to maximize vagal stimulation by combining strain with a rapid change in body position. To perform it, you should first sit or lie down safely. Take a deep breath and blow forcefully against resistance—such as trying to blow into a blocked straw—for about 15 seconds. Immediately afterward, lie flat and raise your legs for another 15 seconds, then return to a comfortable position and breathe normally. This sequence significantly increases the chance of stopping an SVT episode.

The standard Valsalva maneuver is a simpler version of the same concept. It involves taking a deep breath and bearing down as if having a bowel movement for 10 to 15 seconds, then releasing and breathing normally. While easier to perform, it is slightly less effective than the modified version.

Another method is the cold face immersion or diving reflex technique, which uses the body’s natural response to cold. Applying a cold pack or ice wrapped in a cloth to the face—particularly around the eyes and nose—for 10 to 20 seconds can trigger vagal activation. Splashing cold water on the face may have a similar effect. This technique is especially effective in children but can also work in adults.

Forceful coughing can sometimes stimulate the vagus nerve as well. Taking a deep breath and coughing strongly several times in succession may help slow the heart rate, although this method is less reliable than other maneuvers.

Carotid sinus massage is another vagal maneuver, but it should only be performed by trained healthcare professionals. It involves gentle pressure on a specific area of the neck where the carotid artery is located. Because of the risk of stroke in certain individuals, patients should not attempt this maneuver on their own.

What You May Feel During a Vagal Maneuver

If a vagal maneuver is successful, you may feel the heart rate slow abruptly or notice a sudden return to a normal rhythm. Some people experience brief lightheadedness or a flushed sensation, which usually resolves quickly.

When to Seek Medical Help

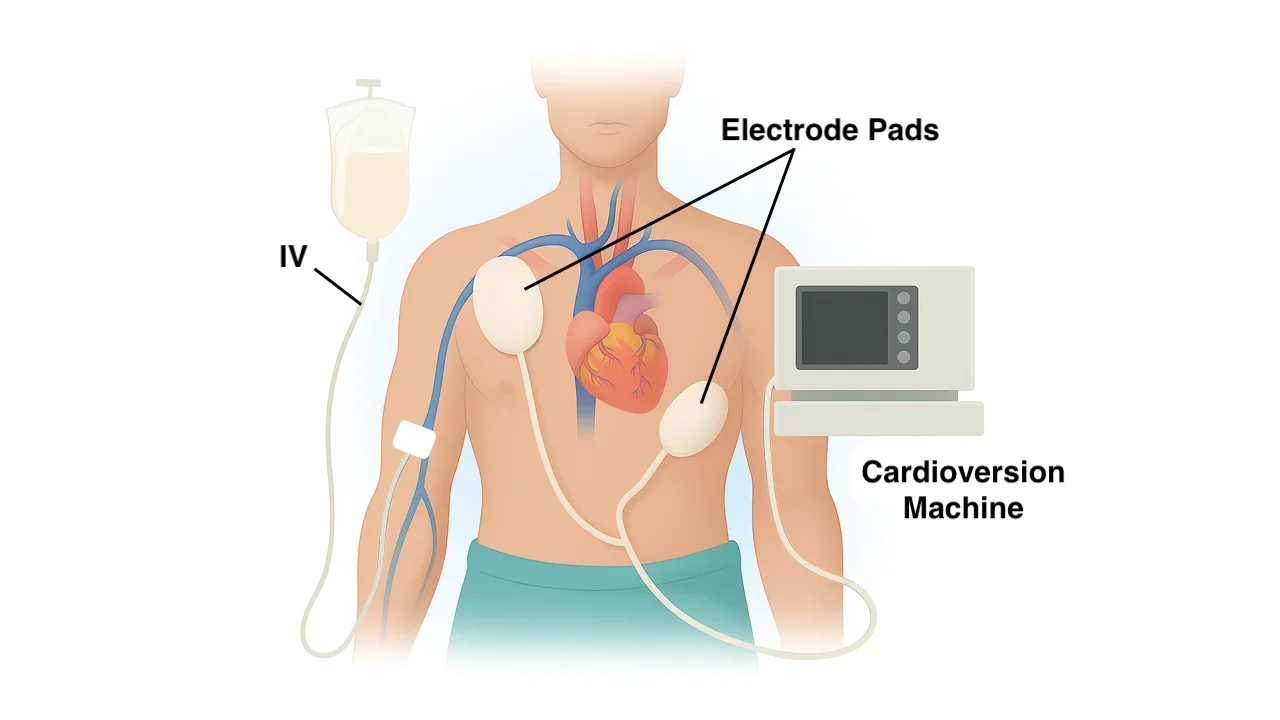

If the rapid heartbeat does not stop after one or two attempts, lasts longer than expected, or is accompanied by chest pain, fainting, severe shortness of breath, or weakness, medical attention should be sought promptly. In these situations, medications or electrical cardioversion may be required.

Safety and Practical Considerations

Vagal maneuvers should always be performed in a safe position to reduce the risk of falling if lightheadedness occurs. They should only be used if recommended by your healthcare provider and after you have been shown the correct technique.

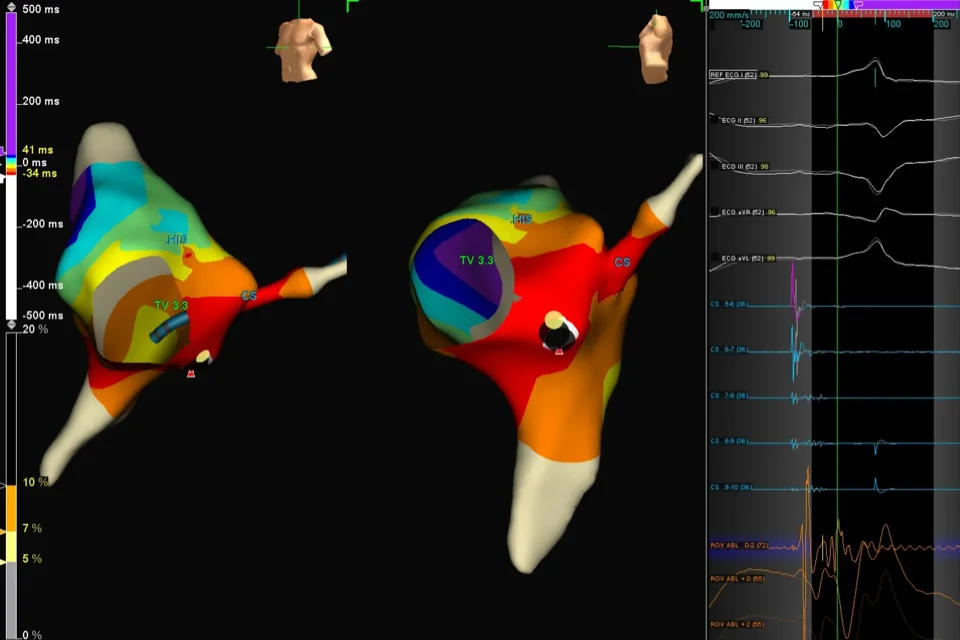

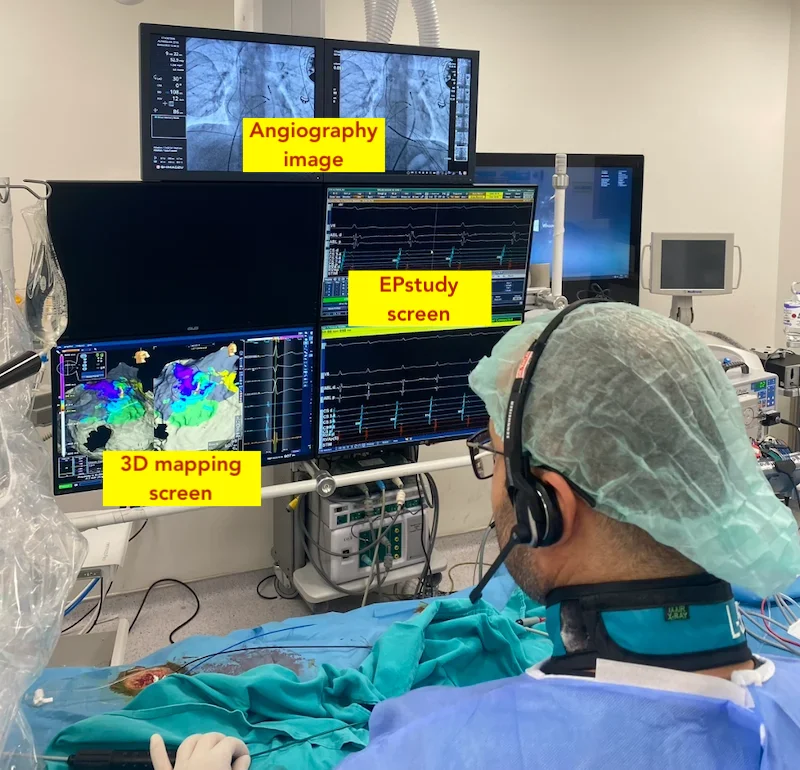

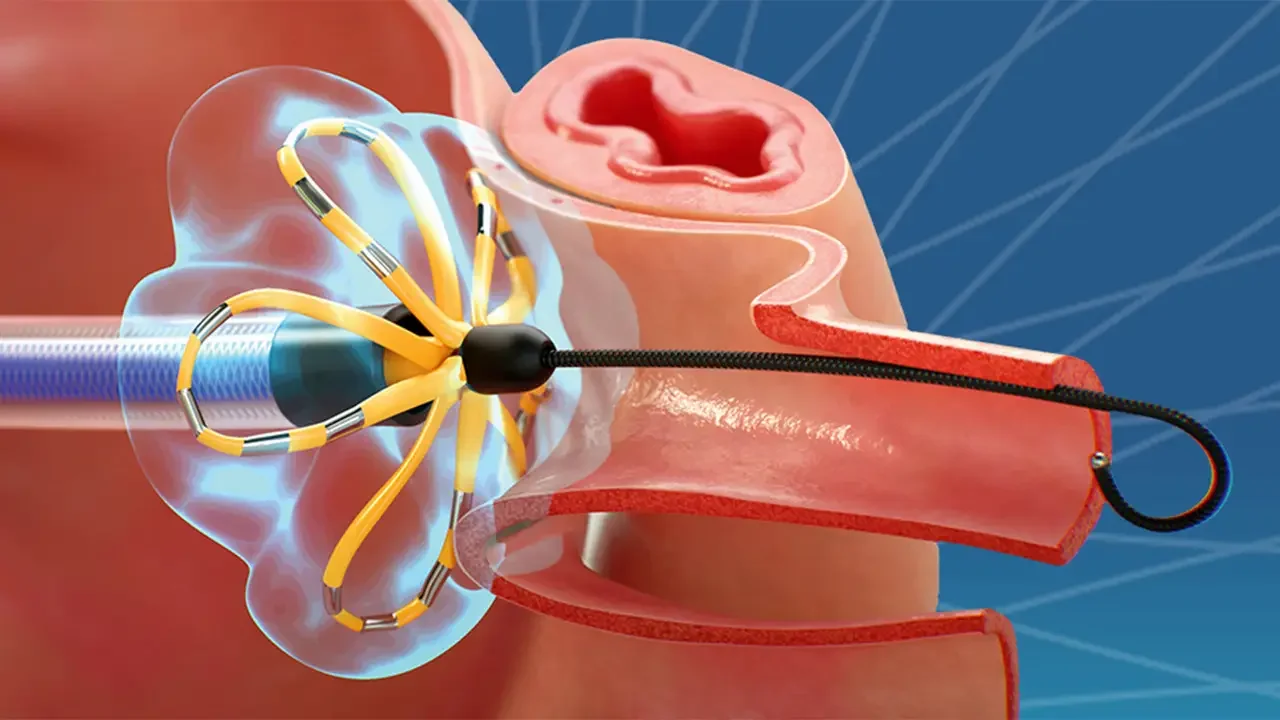

Frequent or recurrent episodes of rapid heart rhythm often require further evaluation and long-term treatment, such as medication or catheter ablation.

In Summary

Vagal maneuvers are simple, patient-controlled techniques that can effectively stop certain rapid heart rhythms by stimulating the vagus nerve. When used appropriately and performed correctly, they offer a safe and empowering way for patients to manage sudden episodes of supraventricular tachycardia.

Reference: Vagal Maneuver