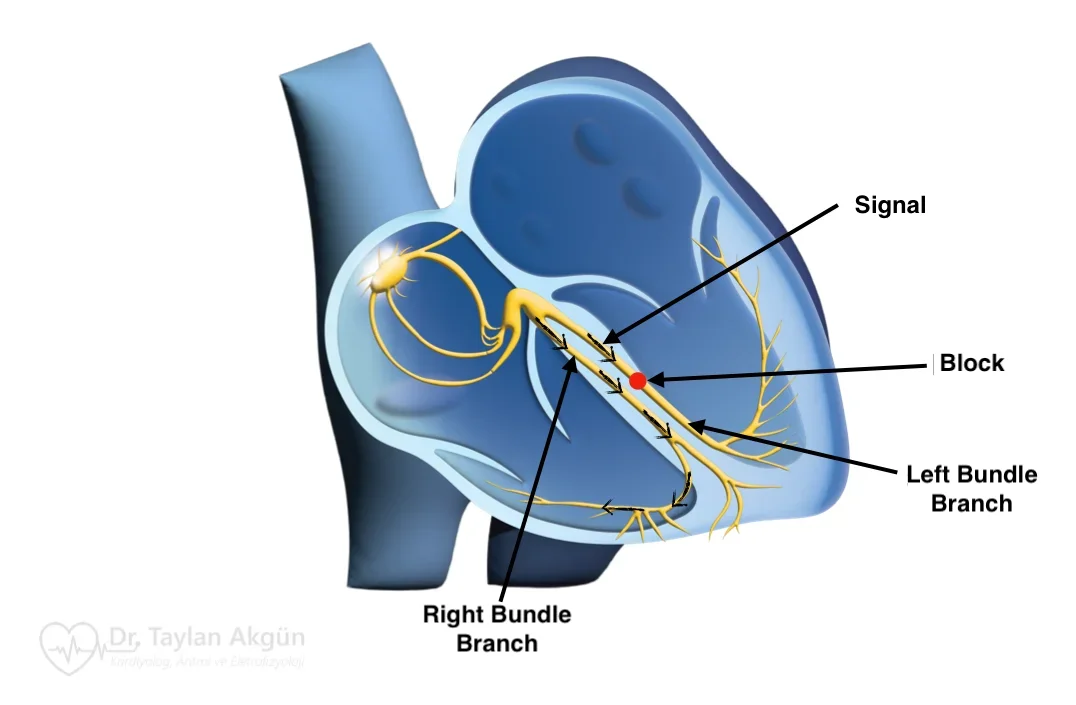

Brugada syndrome is an inherited arrhythmia that affects the heart’s electrical system. Unlike many other cardiac conditions, the heart structure is usually normal. The problem lies in how electrical signals are generated and conducted, particularly in the lower chambers of the heart.

Brugada syndrome is important because, in some individuals, it can increase the risk of dangerous ventricular arrhythmias (VFib). At the same time, many people with Brugada syndrome never experience symptoms and live normal lives. Understanding this balance is key to appropriate management.

How Brugada Syndrome Affects the Heart

The heart relies on carefully regulated electrical currents to maintain a stable rhythm. In Brugada syndrome, abnormalities in these currents—most commonly involving sodium channels—alter how electrical signals travel through the ventricles.

These changes can create conditions in which fast and potentially life-threatening ventricular rhythms occur, particularly during rest, sleep, or fever. The condition does not weaken the heart muscle or block blood flow; it alters electrical stability.

Symptoms of Brugada Syndrome

Many people with Brugada syndrome have no symptoms and are diagnosed only after an abnormal electrocardiogram is discovered. When symptoms do occur, they are usually related to transient rhythm disturbances.

Possible symptoms include:

- Fainting or near-fainting, especially during rest or sleep

- Sudden episodes of dizziness

- Palpitations

- Nocturnal gasping or seizure-like activity

In rare cases, Brugada syndrome may present as sudden cardiac arrest, particularly in individuals who were previously unaware of the condition.

Why Brugada Syndrome Occurs

Brugada syndrome is most often caused by inherited genetic variants that affect ion channels in heart cells. These channels regulate the flow of electrical current that initiates and propagates each heartbeat.

The condition is typically inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern, meaning a single altered gene can be sufficient. However, not everyone with the genetic change develops symptoms or ECG abnormalities.

Certain factors can unmask or worsen Brugada patterns, including fever, dehydration, alcohol, and some medications.

The Brugada ECG Pattern

Brugada syndrome is diagnosed based on characteristic findings on an electrocardiogram. The most specific pattern shows a distinctive elevation in certain ECG leads.

The ECG pattern may not be present all the time. It can appear intermittently or only during specific conditions, such as fever or after exposure to certain drugs. This variability explains why repeated or provocative testing may be needed for diagnosis.

When Brugada Syndrome Is Concerning

Not all individuals with Brugada syndrome have the same risk. Risk assessment focuses on symptoms, family history, and ECG findings.

People who have experienced unexplained fainting, documented ventricular arrhythmias, or cardiac arrest are considered at higher risk. In contrast, individuals who have never had symptoms may be at much lower risk and often do not require invasive treatment.

This risk-based approach prevents unnecessary interventions while protecting those at genuine risk.

How Brugada Syndrome Is Diagnosed

Diagnosis begins with an electrocardiogram. In some cases, medications may be used under controlled conditions to reveal the characteristic ECG pattern if it is not present at baseline.

Additional evaluation may include heart rhythm monitoring, family screening, and genetic testing in selected cases. The goal is to confirm the diagnosis and determine individual risk.

Treatment Options for Brugada Syndrome

There is no treatment that eliminates the genetic cause of Brugada syndrome. Management focuses on reducing arrhythmia risk and preventing sudden cardiac events.

Avoiding medications known to exacerbate Brugada patterns is essential. Prompt treatment of fever is particularly important, as elevated body temperature can trigger dangerous rhythms.

In individuals at high risk, implantation of an Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillator may be recommended. An ICD continuously monitors heart rhythm and can deliver life-saving therapy if a dangerous arrhythmia occurs.

In selected patients with Brugada syndrome who experience recurrent ventricular arrhythmias or frequent ICD shocks despite optimal medical management, catheter ablation may be considered.

In these cases, ablation is typically performed on the outer (epicardial) surface of the heart, targeting abnormal electrical areas responsible for triggering dangerous rhythms. Epicardial ablation does not replace the need for an ICD but may significantly reduce arrhythmia burden and improve quality of life in carefully selected patients treated at experienced centers.

Medications may be used in specific situations to reduce arrhythmia risk, particularly in patients with recurrent events or those who cannot receive an ICD.

Living With Brugada Syndrome

A diagnosis of Brugada syndrome can be frightening, especially when discovered unexpectedly. Education is a central part of care. Understanding which symptoms to watch for and which triggers to avoid allows many people to live safely and confidently.

Family members may also benefit from screening, as early identification can guide preventive strategies.

In Summary

Brugada syndrome is an inherited disorder of the heart’s electrical system that can increase the risk of serious ventricular arrhythmias. While some individuals are at high risk, many remain asymptomatic throughout life. Careful evaluation, risk-based management, and appropriate preventive strategies allow most people with Brugada syndrome to be managed safely and effectively.

Reference: Brugada Syndrome