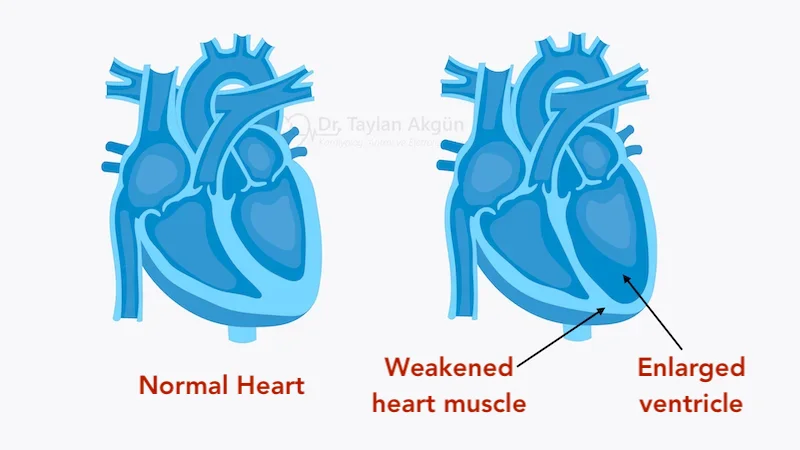

Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) is a condition in which the heart muscle becomes weakened and enlarged, leading to reduced pumping ability. The heart chambers—particularly the left ventricle—stretch and dilate, making it difficult for the heart to contract effectively and deliver enough blood to the body.

DCM is one of the most common forms of cardiomyopathy and a frequent cause of heart failure. It can affect people of all ages and may develop gradually or present suddenly.

How Dilated Cardiomyopathy Affects the Heart

In a healthy heart, the ventricles contract forcefully with each beat. In dilated cardiomyopathy, the heart muscle loses strength and elasticity. As the chambers enlarge, each contraction becomes less efficient.

This reduced pumping function leads to lower blood flow to organs and increased pressure inside the heart. Over time, fluid may accumulate in the lungs, legs, or abdomen, and the risk of rhythm disturbances increases.

Common Causes of Dilated Cardiomyopathy

Dilated cardiomyopathy has many potential causes, and in some cases, no clear cause is identified.

Common causes include genetic predisposition, viral infections affecting the heart muscle, excessive alcohol use, certain chemotherapy drugs, and long-standing uncontrolled high blood pressure. Coronary artery disease and prior heart attacks can also lead to a dilated, weakened heart.

In many patients, DCM is classified as idiopathic, meaning the exact cause remains unknown despite thorough evaluation.

Symptoms of Dilated Cardiomyopathy

Symptoms often develop gradually as heart function declines, but they may worsen suddenly during periods of decompensation.

Common symptoms include:

- Shortness of breath, especially with exertion or when lying flat

- Fatigue and reduced exercise tolerance

- Swelling of the legs, ankles, or abdomen

- Rapid weight gain due to fluid retention

- Palpitations or irregular heartbeat

- Dizziness or fainting

Some individuals may have minimal symptoms early in the disease.

Dilated Cardiomyopathy and Arrhythmias

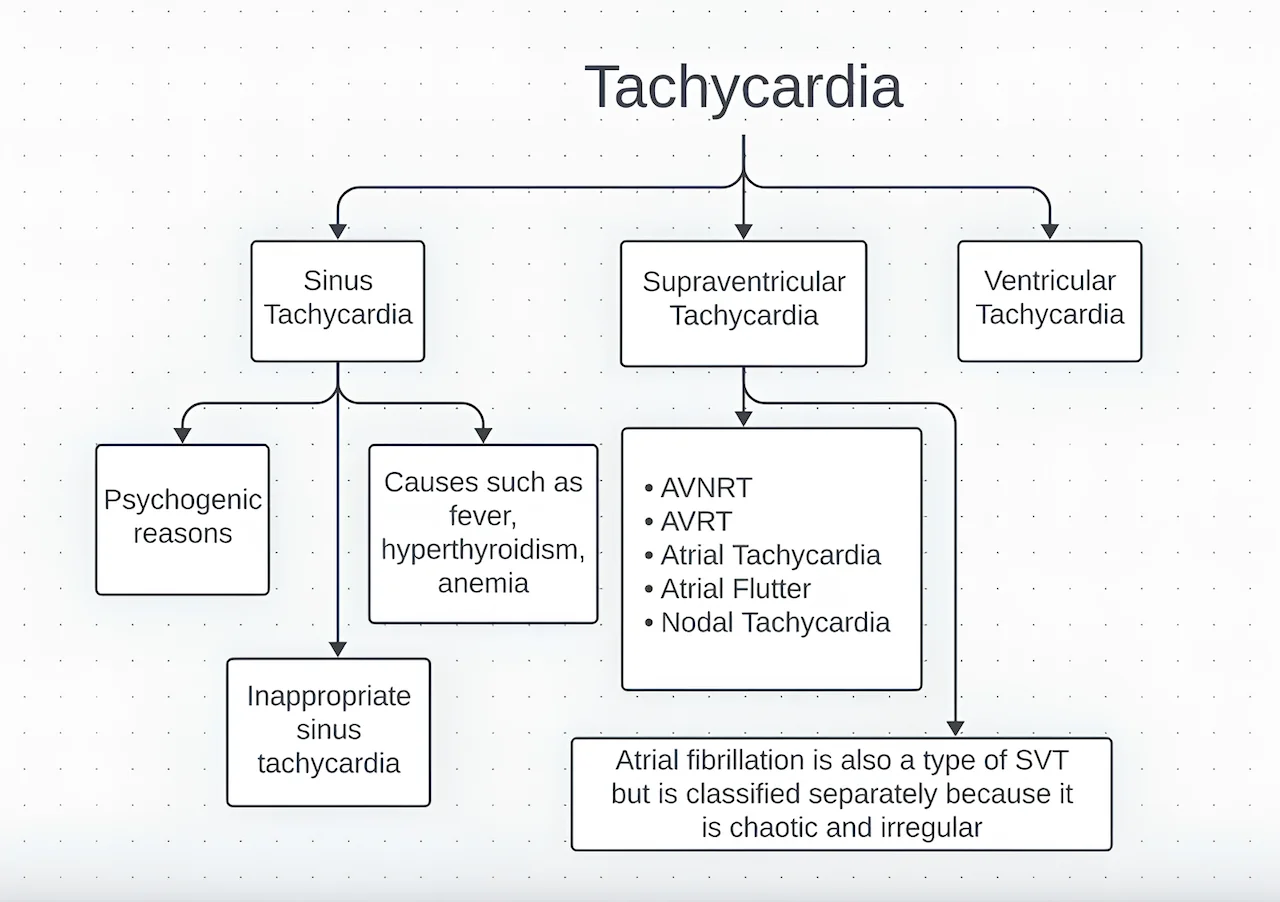

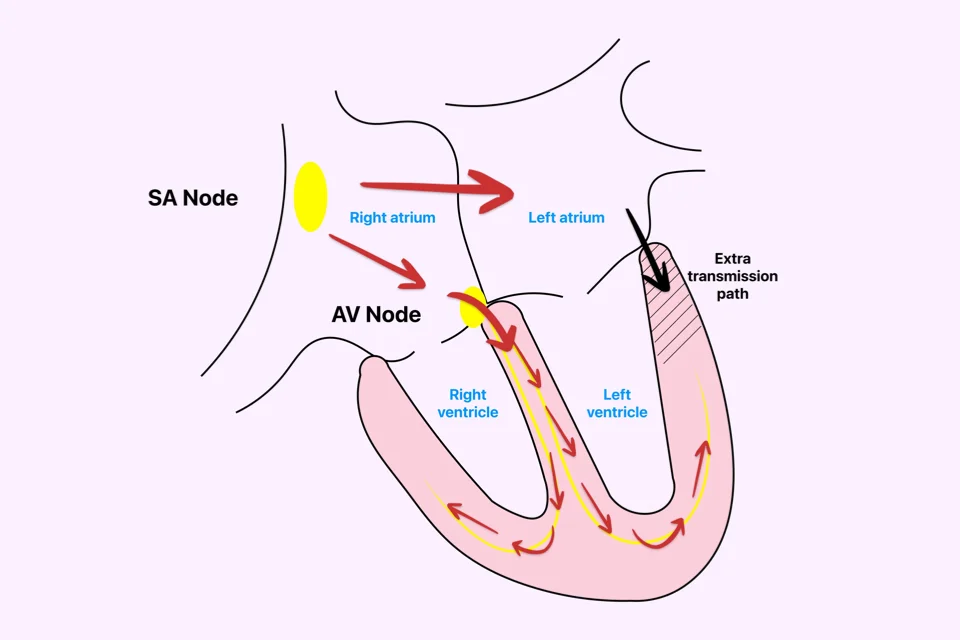

Structural changes and stretching of the heart muscle increase the risk of heart rhythm disorders. Atrial Fibrillation is common in DCM, and ventricular arrhythmias may occur as the disease progresses.

These rhythm disturbances can worsen symptoms and, in some cases, increase the risk of sudden cardiac death.

How Dilated Cardiomyopathy Is Diagnosed

Diagnosis relies on imaging and clinical evaluation. Echocardiography is the primary diagnostic tool, showing enlarged heart chambers and reduced pumping function.

Cardiac MRI may be used to assess scar tissue, inflammation, or underlying causes. Blood tests, electrocardiography, and sometimes genetic testing help identify contributing factors and guide treatment.

Treatment Options for Dilated Cardiomyopathy

Treatment of dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) focuses on improving heart function, relieving symptoms, slowing disease progression, and preventing serious complications such as heart failure progression and sudden cardiac death. Management is almost always multidisciplinary and evolves over time based on disease severity and response to therapy.

Lifestyle Measures and Daily Management

Lifestyle modification is a fundamental part of DCM treatment and supports the effectiveness of medical therapy.

Patients are typically advised to limit salt intake to reduce fluid retention and prevent worsening congestion. Careful fluid management may be recommended, particularly in individuals with recurrent swelling or shortness of breath. Avoidance of alcohol is especially important, as alcohol can directly weaken the heart muscle and worsen DCM.

Regular physical activity at a level appropriate for symptoms is encouraged, while excessive exertion should be avoided during unstable periods. Close follow-up and daily weight monitoring help detect early signs of deterioration and allow timely treatment adjustments.

Medication Therapy

Medications are the cornerstone of treatment for dilated cardiomyopathy and are usually required long term.

Drug therapy aims to:

- Reduce the workload on the heart

- Improve pumping efficiency

- Control fluid buildup

- Suppress harmful hormonal activation

- Reduce the risk of hospitalization and death

Most patients require a combination of medications, which are carefully adjusted over time. Symptom improvement often occurs gradually, and adherence to treatment is critical. Stopping or missing medications can lead to rapid worsening of heart function.

Device-Based Therapies

In selected patients, implantable cardiac devices play a major role in improving outcomes.

Some patients benefit from specialized pacing therapies known as cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT), which improve the coordination of heart contractions when electrical activation is delayed or uncoordinated. This can lead to significant improvement in symptoms and heart function in appropriately selected individuals.

Patients with dilated cardiomyopathy are also at increased risk of dangerous ventricular arrhythmias. For those at higher risk, implantation of an Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillator may be recommended. An ICD continuously monitors heart rhythm and can deliver life-saving therapy if a life-threatening arrhythmia occurs.

Device therapy is used in addition to, not instead of, optimal medical treatment.

Advanced and Specialized Therapies

When dilated cardiomyopathy progresses despite optimal medication and device therapy, advanced treatment options may be considered.

These include specialized intravenous medications, temporary or long-term mechanical circulatory support devices, or evaluation for heart transplantation in carefully selected patients. Such therapies are reserved for advanced stages of disease and are managed in experienced heart failure centers.

Early referral for advanced care is important, as outcomes are better when intervention occurs before irreversible organ damage develops.

Ongoing Monitoring and Long-Term Care

Dilated cardiomyopathy is a chronic condition that requires lifelong follow-up. Regular clinical assessment and imaging allow monitoring of heart function, optimization of therapy, and early detection of complications.

Patient education and active participation in care are essential for long-term stability and quality of life.

Living With Dilated Cardiomyopathy

Many people with dilated cardiomyopathy are able to lead active and fulfilling lives with appropriate treatment and monitoring. Symptom control, medication adherence, and early recognition of changes are key to long-term stability.

Family screening may be advised in inherited cases.

In Summary

Treatment of dilated cardiomyopathy combines lifestyle measures, long-term medication therapy, and—in selected patients—implantable devices or advanced interventions. While the condition can be serious, modern treatment strategies allow many individuals with DCM to achieve meaningful symptom improvement and live active, fulfilling lives.

You may also like to read these:

Reference: Dilated cardiomyopathy