Syncope, commonly known as fainting, is a sudden and temporary loss of consciousness caused by a brief reduction in blood flow to the brain. It usually occurs quickly, lasts a short time, and is followed by a spontaneous and complete recovery.

Although fainting can be frightening—for both the person experiencing it and those witnessing it—not all syncope is dangerous. Some forms are benign and related to reflexes of the nervous system, while others may signal an underlying heart or medical condition that requires prompt evaluation.

What Happens During Syncope

The brain depends on a constant supply of oxygen-rich blood. Even a short interruption can lead to loss of consciousness. In syncope, this interruption is temporary and reversible.

Most people experience warning symptoms just before fainting, such as lightheadedness, nausea, blurred vision, or a feeling of warmth. In some cases, however, syncope occurs without warning, which raises greater concern and requires careful medical assessment.

Common Symptoms Before and After Fainting

Syncope is often preceded by subtle signals that the body is about to lose balance and consciousness. Recognizing these symptoms can help prevent injury.

Typical warning signs include:

- Dizziness or lightheadedness

- Sweating or feeling unusually warm

- Nausea

- Blurred or tunnel vision

- Ringing in the ears

After regaining consciousness, people may feel tired, weak, or slightly confused for a short period. Full recovery usually occurs within minutes.

Why Syncope Occurs

Syncope is not a diagnosis by itself but a symptom with many possible causes. Understanding the underlying mechanism is essential for determining risk and treatment.

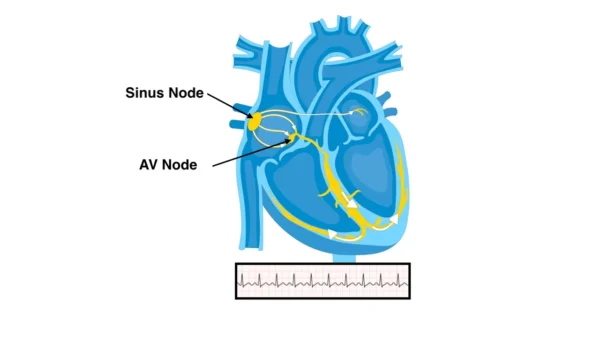

Broadly, syncope occurs when blood pressure drops, heart rate slows excessively, or the heart cannot pump blood effectively for a brief period. These changes can be driven by nervous system reflexes, heart rhythm disturbances, or structural heart disease.

Major Types of Syncope

Different mechanisms lead to different types of syncope. Distinguishing between them is one of the most important steps in evaluation.

Reflex (Vasovagal) Syncope

This is the most common and generally the least dangerous form. It occurs when a reflex causes sudden slowing of the heart rate and dilation of blood vessels, leading to a drop in blood pressure. Triggers may include emotional stress, pain, prolonged standing, dehydration, or seeing blood.

Orthostatic Hypotension

This form occurs when blood pressure drops significantly upon standing. It is often related to dehydration, certain medications, or disorders affecting blood pressure regulation.

Cardiac Syncope

Syncope caused by heart conditions is less common but more serious. It may result from Arrhythmias that are too fast or too slow, or from structural heart problems that limit blood flow. Cardiac syncope often occurs suddenly and may lack warning symptoms.

Because of its potential risk, cardiac syncope always requires thorough evaluation.

When Syncope Is Concerning

Not all fainting episodes are equal. Certain features suggest a higher risk cause and should prompt urgent medical attention.

Syncope is more concerning when it:

- Occurs during exertion or while lying down

- Happens suddenly without warning

- Is associated with chest pain or palpitations

- Occurs in individuals with known heart disease

- Results in significant injury

These features raise suspicion for cardiac causes.

How Syncope Is Evaluated

Evaluation begins with a detailed history and physical examination. Understanding what happened before, during, and after the episode provides critical clues.

Tests may include heart rhythm monitoring, blood pressure measurements in different positions, blood tests, and imaging studies. In selected cases, specialized testing such as a tilt-table test is used to reproduce symptoms and clarify the mechanism.

The goal of evaluation is not only to explain the episode, but also to assess future risk.

Treatment and Prevention

Treatment of syncope depends entirely on the underlying cause. For many people, especially those with benign forms of fainting, the most effective treatment begins with understanding what triggers an episode and how to respond before loss of consciousness occurs.

Responding to Early Warning Signs

Many fainting episodes are preceded by warning symptoms such as dizziness, nausea, sweating, blurred vision, or a feeling of warmth. Learning to recognize these early signals is one of the most important preventive strategies.

At the first sign of symptoms, sitting or lying down can prevent a fall and allow blood flow to the brain to recover. Elevating the legs while lying down helps restore circulation more quickly. If lying down is not possible, tightening the leg, abdominal, and arm muscles or crossing the legs firmly can help raise blood pressure and delay or prevent fainting.

These simple physical responses are especially effective in reflex (vasovagal) syncope and can significantly reduce the risk of complete loss of consciousness and injury.

In selected patients with recurrent and severe reflex (vasovagal) syncope that does not respond to lifestyle measures or medical therapy, a newer treatment option called cardioneuroablation may be considered. This catheter-based procedure targets specific cardiac nerve pathways responsible for excessive reflex slowing of the heart and may reduce or eliminate fainting episodes without the need for a pacemaker.

Lifestyle and Preventive Measures

Adequate hydration is essential, particularly for individuals prone to fainting. Avoiding prolonged standing, especially in warm environments, can reduce episodes. Gradual position changes—from lying to sitting to standing—help prevent sudden drops in blood pressure.

Identifying and avoiding known triggers such as dehydration, skipped meals, excessive heat, emotional stress, or pain plays a key role in prevention. In some individuals, increasing salt intake under medical guidance may be helpful.

Treating the Underlying Cause

When syncope is related to an identifiable medical condition, treatment focuses on correcting that cause.

If fainting is due to low blood pressure or medication effects, adjusting or discontinuing certain drugs may resolve symptoms. Treating anemia, infections, or metabolic conditions can also eliminate episodes.

Cardiac-Related Syncope

When syncope is caused by heart rhythm disturbances or conduction problems, treatment may involve more targeted interventions. Fast or slow Arrhythmias may be treated with medications, cardioversion, or catheter-based procedures depending on the mechanism involved.

In cases where the heart beats too slowly or electrical signals fail to reach the ventricles reliably, implantation of a Pacemaker may be recommended. A pacemaker ensures a stable heart rate and prevents pauses that can lead to fainting.

For individuals at risk of dangerous fast rhythms originating from the ventricles, additional protective devices may be considered after careful evaluation.

Long-Term Management and Follow-Up

Not all patients with syncope require long-term treatment, but regular follow-up is important, especially when the cause is unclear or symptoms recur. Monitoring allows clinicians to reassess risk and adjust management as needed.

Education, reassurance, and individualized care plans empower patients to manage symptoms confidently and safely.

Living With Syncope

Experiencing fainting can be unsettling and may lead to fear of recurrence. Education and reassurance are key components of management. Understanding the cause helps patients regain confidence and reduce anxiety.

In many cases, simple lifestyle adjustments significantly reduce recurrence and improve quality of life.

In Summary

Syncope is a temporary loss of consciousness caused by reduced blood flow to the brain. While many episodes are benign, some reflect serious underlying conditions, particularly heart-related causes. Accurate diagnosis and individualized management are essential to ensure safety and long-term well-being.

Reference: Syncope