What is cardioversion?

In atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, and some supraventricular tachycardias, the heart may beat too fast, irregularly, or in an uncontrolled manner. In such cases, the heart rhythm can be restored to normal either with medications or with a brief electrical shock. This procedure is called cardioversion.

Cardioversion is an effective treatment used to quickly and safely restore an abnormal heart rhythm to normal.

Why is cardioversion performed?

The goals of cardioversion are to:

- Restore your heart rhythm to normal

- Reduce symptoms such as palpitations, shortness of breath, and fatigue

- Help your heart work more efficiently

- Reduce the long-term risk of heart failure and blood clots

A heart that returns to normal rhythm pumps blood more effectively throughout the body, helping you feel better and continue daily activities more comfortably.

Types of cardioversion

There are two main types of cardioversion:

Pharmacologic cardioversion

In this method, medications given intravenously or orally are used to restore the heart rhythm to normal. In some patients, the rhythm can return to normal within a short time using this approach.

Electrical cardioversion

Electrical cardioversion restores the heart rhythm by delivering a brief, controlled electrical current. Short-acting anesthesia is used during the procedure, so no pain or discomfort is felt.

This method is preferred especially for rhythm disorders that have been present for a longer time or do not respond to medications.

How is cardioversion performed?

Cardioversion is usually performed under short-acting sedation (a light sleep state). This ensures that you do not feel pain or discomfort during the procedure.

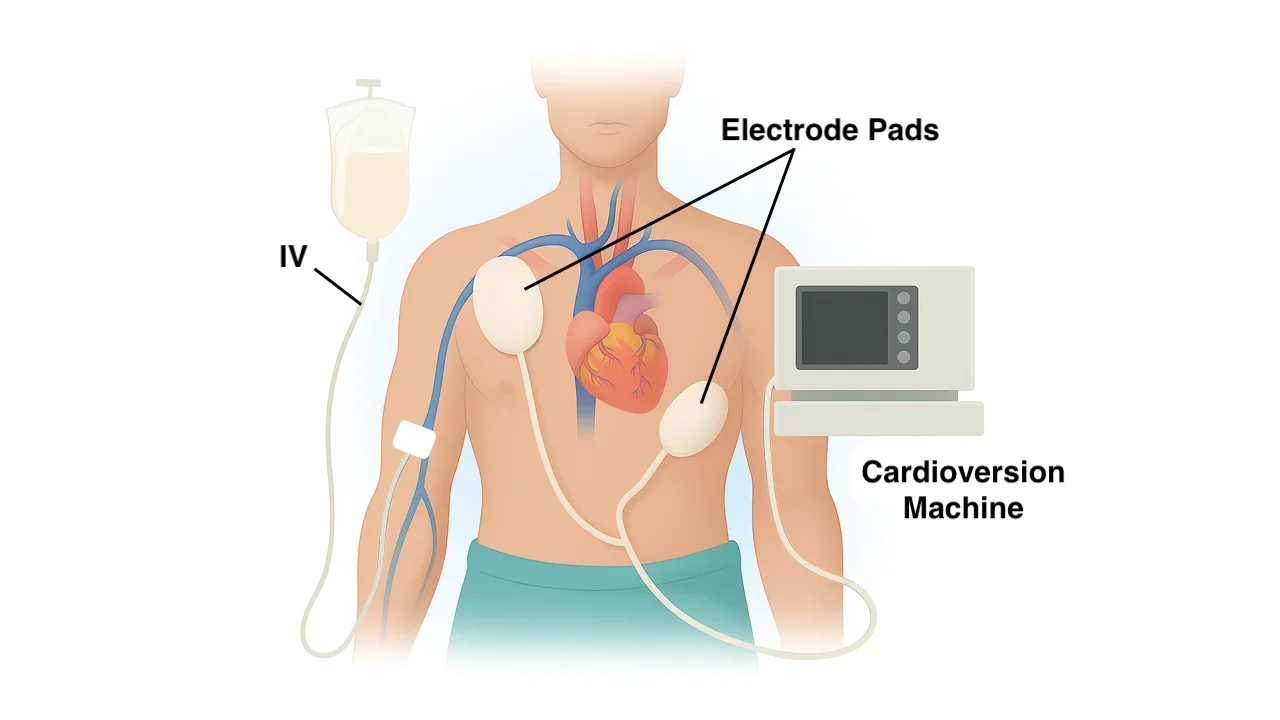

Pads placed on the chest deliver a controlled, very brief electrical current to the heart. This current resets the heart’s electrical activity, allowing the rhythm to return to normal.

The procedure itself takes only a few seconds. Including preparation and recovery, the total hospital stay is usually a few hours.

Most patients are discharged on the same day.

Is preparation required before cardioversion?

Before cardioversion, several evaluations are performed:

- The type and duration of the abnormal rhythm are assessed

- Blood tests are obtained

- A heart ultrasound may be performed if needed

If the rhythm disorder has lasted longer than 48 hours, blood-thinning therapy may be started before the procedure due to the risk of clot formation, or a special ultrasound performed through the esophagus (TEE) may be used to look for clots inside the heart.

You will be asked to fast for 6–8 hours before cardioversion.

What happens after cardioversion?

After cardioversion, a short period of rest is usually sufficient. Most people recover fully within a few hours.

After the procedure:

- Your heart rhythm is checked again

- Heart rate and blood pressure are monitored

- Medications to maintain normal rhythm may be started if needed

In some patients, the rhythm may become abnormal again over time. In such cases, medication therapy, catheter ablation, or repeat cardioversion may be required.

Is cardioversion safe?

When performed in experienced centers, cardioversion is a very safe procedure.

The most common side effects include:

- Mild redness on the chest

- Temporary skin sensitivity

- Mild fatigue

In rare cases, the heart rhythm may temporarily slow down or different rhythm disturbances may occur. For this reason, close monitoring is performed during and after the procedure. The risk of serious complications is very low.

Is cardioversion a permanent solution?

Cardioversion corrects the heart rhythm but does not eliminate the underlying cause of the rhythm disorder.

Therefore:

In some patients, the rhythm may remain normal for a long time

In others, the rhythm may become abnormal again

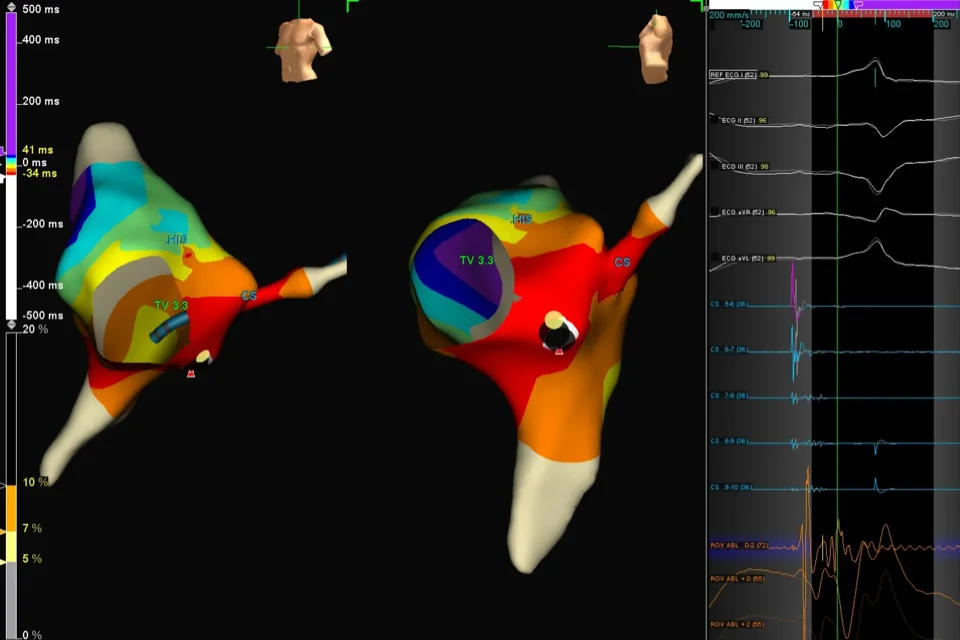

To achieve a more permanent solution, catheter ablation may be required.

Reference: Cardioversion