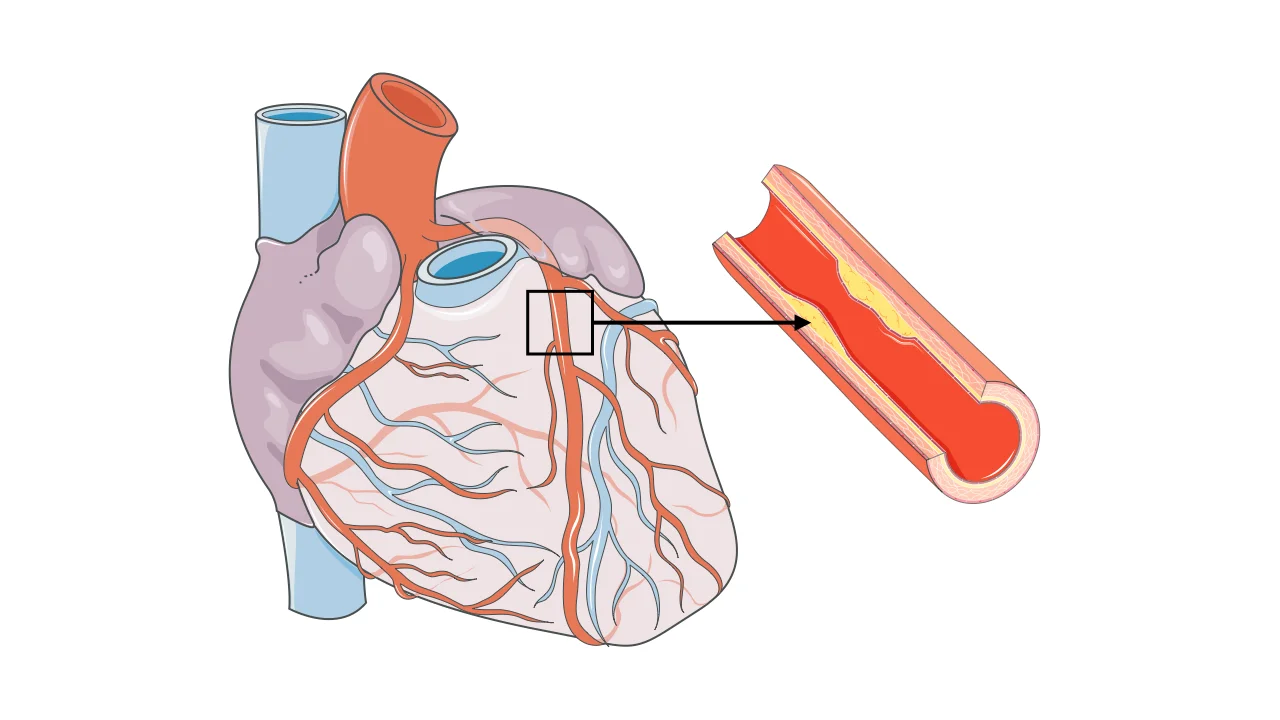

Your heart is a muscle that never rests, beating about 100,000 times daily to circulate blood throughout your body. Like any hardworking muscle, it needs a constant supply of oxygen and nutrients delivered through its own network of blood vessels called coronary arteries. Coronary artery disease develops when these critical arteries become narrowed or blocked by buildup of fatty deposits called plaque. This process, happening silently over decades, reduces blood flow to your heart muscle and can lead to chest pain, heart attacks, or sudden death.

Overview

Coronary artery disease, also called coronary heart disease or ischemic heart disease, occurs when the arteries supplying blood to your heart muscle become narrowed or blocked. This is the most common type of heart disease and the leading cause of death worldwide.

Your heart has three main coronary arteries—the left anterior descending, the left circumflex, and the right coronary artery—that branch into smaller vessels covering the entire heart surface. These arteries deliver oxygen-rich blood to heart muscle, which needs constant nourishment to keep pumping.

The disease begins with a process called atherosclerosis, where fatty deposits called plaque accumulate inside artery walls. This buildup starts in childhood or young adulthood and progresses slowly over decades. Initially, plaque causes no symptoms. As it grows, arteries narrow, restricting blood flow. When narrowing becomes severe—typically 70% or more—blood flow may be adequate at rest but insufficient during exertion when the heart needs more oxygen.

Plaque isn’t just a simple blockage. These deposits contain cholesterol, inflammatory cells, calcium, and other substances. Some plaques are stable, growing slowly and causing gradual narrowing. Others are unstable or “vulnerable,” with thin caps covering softer cores. These unstable plaques can rupture suddenly, triggering blood clot formation that completely blocks the artery within minutes. This is how most heart attacks occur.

The condition manifests in different ways. Stable angina is chest discomfort that occurs predictably with exertion and resolves with rest. Unstable angina is more serious—chest pain occurring at rest or with minimal exertion, often signaling an impending heart attack. Heart attack, or myocardial infarction, occurs when blood flow stops completely, killing heart muscle. Some people have silent ischemia, where reduced blood flow causes no symptoms but still damages the heart over time.

Coronary artery disease affects more than 18 million Americans and causes over 350,000 deaths annually. While the disease becomes more common with age, it’s not an inevitable part of aging—it’s largely preventable through controlling risk factors.

Causes

Coronary artery disease develops through atherosclerosis, a complex process influenced by multiple factors working together over many years.

- High cholesterol, particularly elevated LDL (low-density lipoprotein) cholesterol, is a primary driver. LDL particles deposit cholesterol into artery walls, initiating plaque formation. The higher your LDL and the longer it remains elevated, the more plaque accumulates. Low HDL (high-density lipoprotein) cholesterol also contributes—HDL removes cholesterol from arteries, so low levels mean less protection.

- High blood pressure damages artery walls, making them more susceptible to plaque buildup. The constant force of elevated pressure injures the delicate inner lining of arteries, creating sites where plaque deposits. Hypertension also accelerates atherosclerosis progression.

- Smoking is one of the most powerful risk factors. Chemicals in tobacco smoke damage artery linings, promote blood clotting, reduce oxygen in blood, and cause arteries to constrict. Even secondhand smoke exposure increases risk.

- Diabetes dramatically accelerates atherosclerosis. High blood sugar damages blood vessels and promotes inflammation. People with diabetes develop coronary artery disease earlier and more extensively than those without it.

- Inflammation plays a central role in atherosclerosis. The immune system responds to damage in artery walls, but chronic inflammation actually promotes plaque growth and destabilization. This is why conditions causing systemic inflammation increase coronary disease risk.

- Obesity, particularly excess abdominal fat, increases coronary disease risk through multiple mechanisms—contributing to high blood pressure, diabetes, high cholesterol, and inflammation.

- Physical inactivity allows risk factors to worsen. Sedentary lifestyle contributes to obesity, raises blood pressure, worsens cholesterol profiles, and increases diabetes risk.

- Family history and genetics influence risk. If close relatives developed coronary disease at young ages—typically before 55 in men or 65 in women—your risk increases. Genetic factors affect cholesterol metabolism, blood pressure regulation, and inflammatory responses.

- Advancing age increases risk as more time allows plaque accumulation. Men typically develop coronary disease earlier than women, with risk increasing significantly after age 45 in men and after menopause in women. However, coronary disease is the leading cause of death in both sexes.

- Chronic kidney disease accelerates atherosclerosis through multiple mechanisms including altered mineral metabolism, inflammation, and oxidative stress.

- Sleep apnea, where breathing repeatedly stops during sleep, increases coronary disease risk through effects on blood pressure, inflammation, and oxygen levels.

- Stress, particularly chronic stress, contributes through effects on blood pressure, inflammation, and behaviors like smoking or overeating used to cope with stress.

- Certain autoimmune diseases including rheumatoid arthritis and lupus significantly increase coronary disease risk through chronic inflammation.

Symptoms

Many people with coronary artery disease have no symptoms for years or decades. The disease progresses silently until narrowing becomes severe or a plaque ruptures causing a heart attack.

- Angina, or chest discomfort, is the classic symptom when coronary artery disease causes inadequate blood flow. The sensation varies between individuals—some describe pressure, squeezing, heaviness, or tightness in the chest. Others feel burning, aching, or fullness. Pain isn’t always the right word—many people describe discomfort rather than acute pain.

- Angina typically occurs in the center or left side of the chest behind the breastbone. It can radiate to the left arm, shoulder, neck, jaw, or back. Some people feel it primarily in these radiation sites rather than the chest. Angina typically lasts several minutes, coming on gradually during exertion or emotional stress and easing with rest. This predictable pattern distinguishes stable angina from heart attacks.

- Shortness of breath sometimes occurs alone or with chest discomfort. If your heart can’t pump adequately because of reduced blood flow, fluid backs up in the lungs, causing breathlessness.

- Some people experience fatigue or weakness during activities they previously tolerated well. This reduced exercise tolerance might be the only symptom of significant coronary disease.

- Women, older adults, and people with diabetes sometimes have atypical symptoms. Instead of chest pain, they might experience primarily shortness of breath, unusual fatigue, nausea, or discomfort in the stomach area. These atypical presentations can delay diagnosis because symptoms aren’t recognized as heart-related.

- Heart attack symptoms require immediate emergency attention. Chest pressure or discomfort lasting more than a few minutes or coming and going, often described as an elephant sitting on the chest, is the most common symptom. Associated symptoms include shortness of breath, cold sweats, nausea, lightheadedness, or discomfort radiating to arms, neck, jaw, or back. Some heart attacks cause no chest discomfort at all, presenting only with these associated symptoms—these “silent” heart attacks are more common in women, diabetics, and older adults.

- Some people discover coronary artery disease only when sudden cardiac arrest occurs. The first symptom is collapse from a fatal heart rhythm, which is why prevention and early detection are so critical.

Diagnosis

Diagnosing coronary artery disease involves assessing symptoms, evaluating risk factors, and performing tests to visualize arteries or detect inadequate blood flow.

- Your medical history provides crucial information. Your doctor asks about symptoms, risk factors, family history, and medications. A thorough description of chest discomfort—what triggers it, where you feel it, how long it lasts, what relieves it—helps distinguish angina from other causes of chest pain.

- Physical examination includes checking blood pressure, listening to your heart and lungs, checking pulses, and looking for signs of atherosclerosis in other blood vessels.

- An electrocardiogram records your heart’s electrical activity. While often normal in people with stable coronary disease, it can show evidence of previous heart attacks or inadequate blood flow during symptoms.

- Blood tests check cholesterol levels, blood sugar, kidney function, and markers of heart damage if heart attack is suspected. Troponin, a protein released when heart muscle is damaged, is measured when evaluating possible heart attacks.

- Stress testing evaluates how your heart responds to exertion. You exercise on a treadmill or stationary bike while your heart is monitored with electrocardiograms. If you can’t exercise, medications simulate exercise effects. Changes during stress suggest inadequate blood flow. Nuclear imaging or echocardiography performed during stress provides more detailed information about which areas of heart muscle aren’t receiving adequate blood.

- CT coronary angiography uses CT scanning with contrast dye to visualize coronary arteries non-invasively. This test shows whether plaque is present, where it’s located, and how severe narrowing is. It’s increasingly used for initial evaluation of possible coronary disease.

- Coronary calcium scoring is a CT scan without contrast that measures calcium in coronary arteries. The amount of calcium correlates with overall plaque burden and helps assess risk, though it doesn’t show how severely arteries are narrowed.

- Cardiac catheterization, also called coronary angiography, is the gold standard for diagnosing coronary artery disease. A thin tube is threaded through blood vessels, usually from the wrist or groin, to the heart. Contrast dye is injected while X-ray videos show dye flowing through coronary arteries, clearly revealing blockages, their location, and severity. This invasive test carries small risks but provides definitive information and allows treatment during the same procedure.

- Intravascular ultrasound or optical coherence tomography can be performed during catheterization, using tiny probes inside arteries to create detailed images of plaque composition and artery walls.

Treatment

Coronary artery disease treatment aims to relieve symptoms, slow disease progression, and prevent heart attacks through lifestyle changes, medications, and sometimes procedures.

- Lifestyle modifications form the foundation. Quit smoking immediately—this is the single most important change. Smoking cessation reduces heart attack risk dramatically within months. Adopt a heart-healthy diet low in saturated fats, trans fats, and cholesterol, emphasizing fruits, vegetables, whole grains, lean proteins, and healthy fats. The Mediterranean diet shows particular benefit. Exercise regularly—aim for at least 150 minutes of moderate activity weekly. Maintain healthy weight through diet and exercise. Manage stress through relaxation techniques, adequate sleep, and addressing sources of chronic stress.

- Medications manage risk factors and prevent complications. Statins lower cholesterol and stabilize plaque, dramatically reducing heart attack risk. They’re recommended for most people with coronary disease regardless of cholesterol levels. Aspirin prevents blood clots, reducing heart attack risk. Other antiplatelet drugs like clopidogrel are used in specific situations. Beta-blockers slow heart rate and reduce blood pressure, decreasing oxygen demand and improving survival after heart attacks. ACE inhibitors or ARBs lower blood pressure and have additional protective effects on blood vessels. Nitroglycerin relieves angina quickly by dilating blood vessels. Long-acting nitrates help prevent angina. Ranolazine reduces angina in people who can’t tolerate or don’t respond adequately to other medications.

- The medication regimen is typically lifelong. These drugs don’t cure coronary disease but control it and prevent progression. Never stop medications without consulting your doctor.

- Percutaneous coronary intervention, commonly called angioplasty or stenting, opens blocked arteries. During cardiac catheterization, a balloon is inflated inside the narrowed artery, compressing plaque and widening the passage. A stent—a tiny mesh tube—is placed to keep the artery open. Drug-eluting stents slowly release medications that prevent the artery from narrowing again. This procedure relieves angina and, during heart attacks, can be lifesaving. It’s performed through small punctures, not requiring open surgery. Most people go home the next day.

- Coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) is open-heart surgery where blood vessels taken from your leg, chest, or arm are used to create new routes around blocked coronary arteries. Bypass surgery is recommended when multiple arteries are severely blocked, when the left main coronary artery is affected, or when anatomy isn’t suitable for stenting. Recovery requires several weeks, but the procedure provides excellent long-term results, particularly in people with diabetes or complex disease.

- Cardiac rehabilitation programs combine supervised exercise, education, and counseling to help you recover from procedures and adopt heart-healthy habits. These programs significantly improve outcomes and quality of life.

- For refractory angina not responding to medications or procedures, enhanced external counterpulsation uses inflatable cuffs on the legs to improve blood flow to the heart. Spinal cord stimulation can reduce angina severity in select patients.

What Happens If Left Untreated

Untreated coronary artery disease progressively worsens, with potentially devastating consequences.

- Heart attacks become increasingly likely as plaque accumulates and unstable plaques rupture. Without treatment, people with significant coronary disease face high risk of heart attack within years. Heart attacks kill heart muscle permanently, and extensive damage leads to heart failure.

- Chronic ischemia, even without heart attacks, can gradually weaken heart muscle, leading to heart failure. The heart becomes less efficient at pumping, causing shortness of breath, fatigue, and fluid retention.

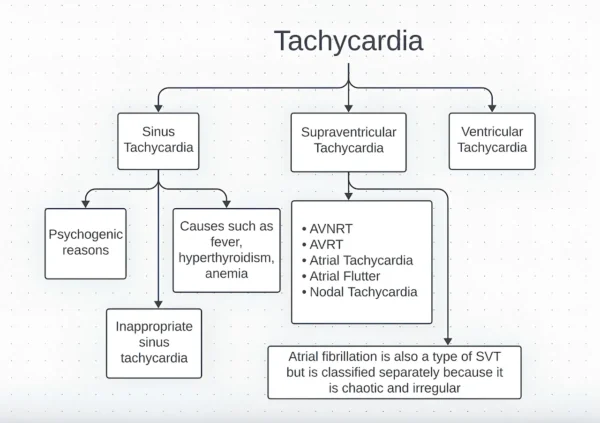

- Dangerous heart rhythms can develop when heart muscle doesn’t receive adequate blood flow. Ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation cause sudden cardiac arrest and death without immediate defibrillation.

- Progressive disability from angina limits activities. Simple tasks become difficult or impossible as chest pain occurs with minimal exertion. Quality of life deteriorates significantly.

- Silent ischemia damages the heart without warning symptoms. Some people suffer multiple small heart attacks over time without realizing it, accumulating damage that eventually causes heart failure.

- Sudden cardiac death can be the first manifestation of coronary disease. Roughly half of men and two-thirds of women who die suddenly from coronary disease had no previous symptoms.

- Life expectancy is significantly shortened. Five-year mortality rates for untreated severe coronary disease exceed 30-40%, much higher than many cancers.

What to Watch For

If you have coronary artery disease or risk factors, recognizing certain symptoms requires immediate action.

- Call emergency services immediately for chest discomfort lasting more than a few minutes or that goes away and returns. Don’t wait to see if it improves—heart attack treatment is most effective when started quickly. Time is heart muscle.

- Seek emergency care for chest discomfort with shortness of breath, cold sweats, nausea, lightheadedness, or discomfort radiating to arm, neck, jaw, or back. These combinations suggest heart attack.

- Women, older adults, and diabetics should seek emergency care for unusual shortness of breath, overwhelming fatigue, or upper stomach discomfort lasting more than a few minutes, even without chest pain. These atypical presentations can be heart attacks.

- Contact your doctor promptly if stable angina patterns change—occurring more frequently, with less exertion, lasting longer, or feeling more severe. These changes suggest unstable angina and increased heart attack risk.

- Report new symptoms like shortness of breath, unusual fatigue, or swelling in legs. These might indicate worsening coronary disease or developing heart failure.

- If you take nitroglycerin for angina and symptoms don’t improve after one dose, or if you need nitroglycerin more frequently than usual, contact your doctor.

- Don’t ignore symptoms because you’re busy, don’t want to bother anyone, or think they’ll pass. Heart attack treatment is time-sensitive—every minute matters.

Potential Risks and Complications

Coronary artery disease and its treatments carry various risks.

- Heart attack is the most serious complication. Extent of damage depends on which artery is blocked, how quickly blood flow is restored, and how much heart muscle is affected.

- Heart failure can result from one large heart attack or multiple smaller ones that cumulatively damage enough muscle to impair pumping function.

- Arrhythmias range from benign extra beats to life-threatening ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation. Damaged heart muscle is electrically unstable.

- Cardiogenic shock occurs when severely damaged heart muscle can’t pump enough blood to sustain vital organs. This medical emergency has high mortality even with aggressive treatment.

- Treatment complications include bleeding, allergic reactions to contrast dye, kidney damage from dye, blood vessel damage at catheterization sites, and rarely stroke or heart attack caused by the procedures themselves. Stents can cause blood clots if antiplatelet medications aren’t taken as prescribed—never stop these medications without consulting your doctor. Bypass surgery carries risks of infection, bleeding, stroke, and prolonged recovery.

- Medication side effects vary by drug. Statins can cause muscle aches and rarely serious muscle breakdown. Aspirin increases bleeding risk. Beta-blockers might cause fatigue or worsen asthma. Each medication has potential side effects that should be discussed with your doctor.

Diet and Exercise

Lifestyle modifications are as important as medications for managing coronary disease and preventing progression.

- Adopt a heart-healthy eating pattern. The Mediterranean diet—rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, nuts, fish, and olive oil—shows particular benefit for cardiovascular health. Limit saturated fats found in red meat and full-fat dairy, eliminate trans fats found in many processed foods, and reduce cholesterol intake. Increase fiber through fruits, vegetables, and whole grains. Choose lean proteins including fish, poultry, and plant-based sources. Use healthy fats from olive oil, avocados, nuts, and fatty fish.

- Reduce sodium to less than 2,300 mg daily, particularly if you have high blood pressure. Most dietary sodium comes from processed and restaurant foods rather than salt added at the table.

- Limit added sugars and refined carbohydrates, which contribute to obesity, diabetes, and unfavorable cholesterol profiles.

- Moderate alcohol consumption might have modest cardiovascular benefits, but excessive drinking is harmful. If you drink, limit to one drink daily for women and two for men.

- Exercise regularly with your doctor’s approval. Start slowly if you’ve been sedentary. Walking is excellent—begin with short distances and gradually increase. Aim for at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity weekly. Activities like brisk walking, swimming, cycling, or dancing all benefit cardiovascular health. Add strength training twice weekly. If you have angina, learn what level of activity triggers symptoms and stay below that threshold. Cardiac rehabilitation programs provide supervised exercise in a safe environment.

- Exercise improves cholesterol, lowers blood pressure, helps control weight, reduces diabetes risk, and improves mental health. It’s one of the most powerful interventions for coronary disease.

- Don’t shovel snow if you have coronary disease. This strenuous activity in cold weather commonly triggers heart attacks in susceptible individuals.

Prevention

While some risk factors like family history and age can’t be changed, coronary artery disease is largely preventable through controlling modifiable risk factors.

- Don’t smoke. If you do, quit now. Smoking cessation is the single most impactful change you can make. Benefits begin within hours of quitting and continue accumulating over years.

- Control blood pressure through lifestyle measures and medications if needed. Target is typically below 130/80 mm Hg, sometimes lower based on individual circumstances.

- Manage cholesterol through diet and medications if lifestyle changes aren’t sufficient. Target LDL cholesterol varies based on overall risk, but lower is generally better for preventing coronary disease.

- Control diabetes carefully. Maintain blood sugar as close to normal as safely possible through diet, exercise, and medications.

- Maintain healthy weight through balanced eating and regular physical activity. Even modest weight loss—5-10% of body weight—provides significant health benefits.

- Exercise regularly. Physical activity benefits cardiovascular health through multiple mechanisms beyond weight control.

- Eat a heart-healthy diet emphasizing whole foods and minimizing processed foods high in unhealthy fats, sodium, and added sugars.

- Manage stress through healthy coping mechanisms rather than smoking, overeating, or excessive alcohol consumption.

- Get adequate sleep. Poor sleep quality and sleep deprivation increase cardiovascular risk. Treat sleep apnea if present.

- Stay current with medical care. Regular checkups allow early detection and treatment of risk factors before coronary disease develops.

- Know your numbers—cholesterol levels, blood pressure, blood sugar, and body mass index. Understanding where you stand motivates action.

Key Points

- Coronary artery disease develops over decades as plaque accumulates inside arteries supplying your heart muscle. This process often causes no symptoms until blockages become severe or plaque ruptures causing a heart attack.

- The disease is largely preventable through controlling risk factors. Not smoking, managing blood pressure and cholesterol, controlling diabetes, maintaining healthy weight, and exercising regularly dramatically reduce your risk.

- Chest discomfort or pressure during exertion that improves with rest suggests stable angina. This requires medical evaluation but isn’t immediately life-threatening. Chest discomfort at rest or lasting more than a few minutes suggests heart attack and requires immediate emergency care.

- Modern treatments are highly effective. Medications can dramatically reduce heart attack risk and slow disease progression. Stenting or bypass surgery relieve symptoms and, in specific situations, improve survival.

- Treatment is lifelong. Coronary artery disease is a chronic condition requiring ongoing medication, lifestyle modifications, and regular medical follow-up. It’s controlled, not cured.

- Never stop medications without consulting your doctor, particularly aspirin, antiplatelet drugs, or statins after stenting. Stopping these medications can cause stent blood clots with potentially fatal consequences.

- Women, older adults, and people with diabetes sometimes have atypical symptoms without classic chest pain. Any concerning symptoms warrant evaluation regardless of how “typical” they seem.

- Heart attack treatment is time-sensitive. Calling emergency services immediately when symptoms begin dramatically improves outcomes. Never drive yourself to the hospital during a suspected heart attack.

- Cardiac rehabilitation after heart attacks or procedures significantly improves outcomes. These programs help you safely increase activity, adopt healthy habits, and recover physically and emotionally.

- Work closely with a cardiologist who can guide your treatment. Coronary artery disease management has become increasingly complex and individualized. Your doctor helps you navigate medication choices, determine if procedures are needed, and optimize your overall cardiovascular health. The goal is not just prolonging life but maintaining quality of life—staying active, independent, and able to do the things you enjoy for as long as possible.

Reference: Coronary artery disease