Ventricular fibrillation (VFib) is a very dangerous condition where your heart’s lower chambers (ventricles) suddenly start quivering uncontrollably instead of contracting normally. This quivering stops the heart from pumping blood to your body, causing blood circulation to cease immediately. You will lose consciousness within seconds, marking a sudden cardiac arrest. Since VFib is the main cause of most sudden cardiac deaths, rapid recognition and treatment with an electrical shock (defibrillator) is crucial. Having immediate access to a defibrillator gives you the best chance of survival and a return to a healthy life.

Overview

Ventricular fibrillation is a chaotic, disorganized heart rhythm where your heart’s lower chambers (ventricles) quiver rapidly and irregularly instead of contracting normally. When this happens, there is no effective pumping—blood circulation stops completely, leading to immediate sudden cardiac arrest.

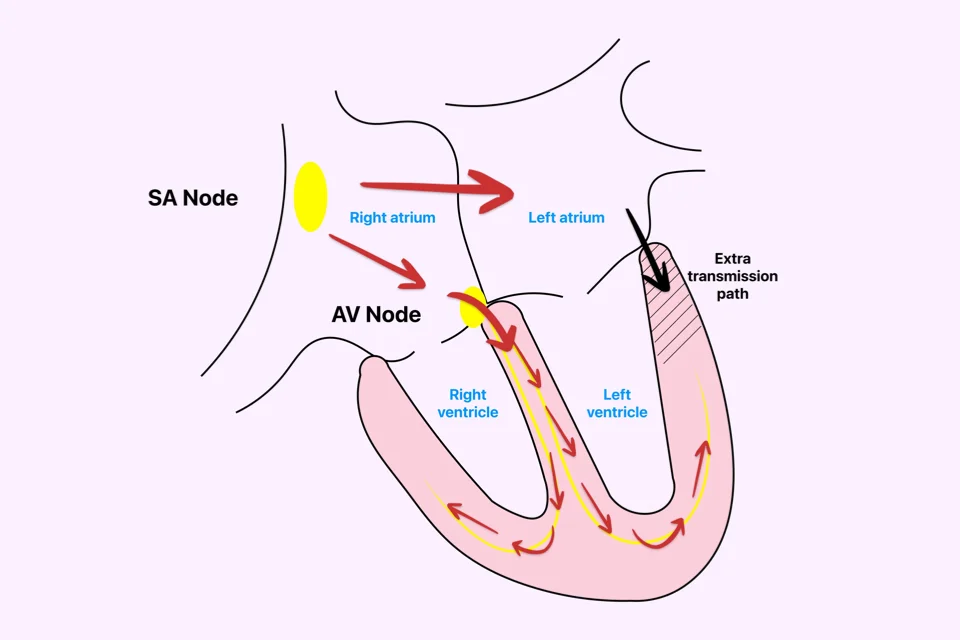

In a normal rhythm, the electrical signals from your heart’s natural pacemaker travel in an orderly way, causing the lower chambers to contract and pump blood efficiently. In VFib, this order is lost. Instead, multiple areas within the lower chambers fire rapid, chaotic electrical signals. Because of this chaotic electrical storm, the heart muscle fibers twitch independently rather than contracting together as one unit. The heart just uselessly quivers.

This rhythm is incompatible with life. When your heart fibrillates, it is not pumping, and your blood pressure instantly drops to zero. Your brain runs out of oxygen, causing you to lose consciousness within 10-15 seconds. Without circulation, permanent brain damage starts after 4-6 minutes. After 10 minutes, survival becomes very rare, even with aggressive resuscitation efforts.

Ventricular fibrillation is the cause of the vast majority of sudden cardiac deaths. If someone suddenly collapses, is unresponsive, is not breathing normally, and has no pulse, it is considered cardiac arrest due to VFib until proven otherwise.

The only effective treatment is defibrillation—delivering an electrical shock that temporarily stops all electrical activity in the heart. This allows your heart’s natural pacemaker to potentially take back control and restore a normal, pumping rhythm. CPR (cardiac massage) alone cannot convert VFib to a normal rhythm, but it maintains some blood flow to the brain and heart, buying vital time until a defibrillator arrives.

Your survival depends almost entirely on how quickly defibrillation occurs. With immediate defibrillation within the first minute or two, survival rates can be very high, exceeding 70-90%. Every minute of delay reduces survival by about 7-10%. After 10 minutes without defibrillation, survival is rare.

This is why Automated External Defibrillators (AEDs) have been placed in public locations like airports, malls, and gyms. These devices allow bystanders to deliver life-saving shocks within minutes, dramatically improving the chance of surviving a sudden cardiac arrest.

Causes

Ventricular fibrillation results from severe electrical instability in the heart, and this is typically due to underlying heart disease or specific triggers.

- Heart attacks are the most common cause. When the arteries supplying your heart (coronary arteries) become blocked, the heart muscle is cut off from oxygen-rich blood. This oxygen-deprived tissue becomes electrically unstable. VFib often occurs during the first hour of a heart attack, sometimes as the very first symptom. This explains why many people die suddenly from heart attacks before they can even reach the hospital.

- Scarring from previous heart attacks creates permanently abnormal tissue. These scars disrupt normal electrical pathways and can trigger VFib, sometimes years after the initial heart attack.

- Conditions like cardiomyopathy, where the heart muscle is diseased or damaged, increase the risk. Muscle diseases of the heart make it electrically unstable and prone to chaotic rhythms.

- Severe heart failure from any cause creates conditions where VFib is much more likely. The stretched, weakened heart muscle becomes prone to chaotic electrical activity.

- Inherited conditions affecting the heart’s electrical system can cause VFib in young people with structurally normal hearts. These genetic diseases can trigger sudden VFib, sometimes during exercise or sleep.

- Other less common causes include high-voltage electrocution, severe electrolyte imbalances (especially very low potassium or magnesium), drug toxicity (overdose), and sometimes, a sudden blunt impact to the chest at a precise moment in the heart cycle (commotio cordis).

- Sometimes, tragically, ventricular fibrillation occurs without any identifiable cause in people whose hearts appear normal. Finding the reason guides the treatment to prevent recurrence and offers hope for future management.

Symptoms

Ventricular fibrillation causes immediate cardiac arrest—there are no warning symptoms once it starts because circulation stops instantly.

- The person suddenly collapses, becoming completely unresponsive within seconds. They will not respond to shouting or shaking.

- Breathing stops or becomes infrequent, with gasping and ineffective breaths (called agonal breathing).

- No pulse can be felt. Blood pressure drops to zero immediately.

- The skin becomes pale or blue-gray as oxygen levels plummet.

This entire sequence happens within seconds. One moment the person seems fine, the next they have collapsed unconscious. This sudden collapse without warning is the hallmark of cardiac arrest from VFib.

However, some people may experience warning symptoms in the minutes, hours, or days before VFib occurs, especially if it’s triggered by a heart attack or unstable heart disease. These warnings include:

- Chest pain or pressure (suggesting a heart attack)

- Palpitations or a fluttering sensation in the chest

- Dizziness or lightheadedness

- Shortness of breath

These are not symptoms of VFib itself, but of the serious underlying conditions that can set the stage for it.

Diagnosis

Diagnosing ventricular fibrillation requires identifying the heart rhythm, which is typically done by first responders during emergency resuscitation efforts.

When someone collapses in cardiac arrest, bystanders should check for responsiveness and breathing. If the person is unresponsive and not breathing normally, cardiac arrest is assumed, and CPR should begin immediately. Do not waste time trying to check for a pulse—if someone collapses unconscious and isn’t breathing, start chest compressions right away.

An Automated External Defibrillator (AED) or a manual defibrillator is attached as quickly as possible. These devices analyze the heart rhythm using electrode pads placed on the chest. If ventricular fibrillation is detected, the device will charge and prompt for the shock delivery.

On an Electrocardiogram (ECG), ventricular fibrillation appears as chaotic, irregular waveforms with no recognizable heartbeats. The emergency team will use the ECG reading to confirm the need for a shock.

After successful resuscitation, an extensive evaluation is performed to determine the exact cause of the VFib. This often includes:

- ECGs to look for signs of a heart attack or electrical abnormalities

- Blood tests to check for heart muscle damage (troponin) and electrolyte levels

- Echocardiography (Echo) to look at the heart’s structure and function

- Coronary Angiography to see if the heart arteries are blocked

If no obvious cause is found, further testing might include a Cardiac MRI to look for subtle muscle disease or genetic testing for inherited conditions. Understanding the cause is the key to guiding long-term treatment and preventing future episodes.

Treatment

Treatment has two crucial phases: First, emergency treatment to restore a normal rhythm and prevent death, and second, long-term treatment to prevent the rhythm from happening again.

Emergency Treatment

- Act Immediately: Recognition of cardiac arrest must be instant—every second counts. Call emergency services immediately or have someone else call while you begin CPR.

- Start CPR: Push hard and fast on the center of the chest—at least 2 inches deep at a rate of 100-120 compressions per minute. CPR maintains some blood flow to the brain and heart, buying time until a defibrillator arrives.

- Defibrillation is the Cure: The electrical shock is the only treatment that can convert VFib back to a normal rhythm. AEDs can be used by anyone; the device provides clear voice prompts guiding you through every step. After the shock, immediately resume CPR for two minutes before the device analyzes the rhythm again.

Long-Term Treatment

Once a normal rhythm is restored, the focus shifts to preventing recurrence:

- If a heart attack triggered it, emergency angioplasty is performed to open blocked arteries.

- For people who survive cardiac arrest from VFib, an Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillator (ICD) is almost always recommended. This is a small device placed under the skin that continuously monitors your heart rhythm and automatically delivers shocks if VFib or another dangerous rhythm occurs, offering immediate life-saving treatment without needing bystander help.

- If inherited conditions caused the VFib, specific treatments exist, such as certain medications (like beta-blockers) and avoiding specific triggers.

- If structural heart disease (like heart failure) was the cause, treating the underlying condition aggressively reduces the future risk.

What Happens Without Treatment

Ventricular fibrillation is immediately fatal without treatment. There are no exceptions—if the rhythm is not converted to something compatible with life within minutes, death is certain.

- Brain damage begins within 4-6 minutes of blood circulation stopping. The brain is extremely sensitive to oxygen deprivation, and permanent neurological damage becomes increasingly likely with each passing minute.

- After 10 minutes without effective circulation, survival becomes very rare, even with aggressive resuscitation efforts.

Even with bystander CPR, which maintains a minimal amount of circulation, defibrillation is still necessary. CPR alone cannot convert VFib—it only buys time until a defibrillator is available, but it cannot restore a normal rhythm.

This is why the chain of survival is so critical: immediate recognition of cardiac arrest, immediate CPR, rapid defibrillation, and advanced care. Every link must be strong to maximize the chance of a positive outcome. Communities with widespread CPR training and publicly accessible AEDs have much higher survival rates than those without these resources.

Prevention

Preventing ventricular fibrillation means addressing the conditions that cause it in the first place, giving you control over your heart health.

- If you have coronary artery disease, controlling your risk factors reduces your risk of a heart attack and therefore reduces the risk of VFib. This includes managing high blood pressure and cholesterol, quitting smoking, controlling diabetes, and maintaining a healthy weight through exercise.

- For people who have had a heart attack, medications like beta-blockers and statins are essential to reduce the risk of a future heart attack and sudden cardiac arrest.

- ICDs prevent death from VFib in high-risk individuals. These devices are recommended for survivors of cardiac arrest from VFib and for people with severely weakened hearts or inherited conditions that put them at high risk for sudden death.

- Treating conditions like heart failure aggressively with medications and lifestyle changes reduces the electrical instability in the heart.

- For inherited conditions, identifying at-risk family members through screening and genetic testing allows protective measures to be put in place before VFib can occur.

What Bystanders Should Do

If someone collapses and is unresponsive, you should assume cardiac arrest and act immediately.

- Check for Responsiveness: Shout and tap their shoulder. If they don’t respond, assume cardiac arrest.

- Call Emergency Services: Call 911 (or your local emergency number) immediately or have someone else call while you begin CPR. Put the phone on speaker so you can receive instructions while working.

- Start CPR Immediately: Place the heel of one hand on the center of the chest, place your other hand on top, and push hard and fast—at least 2 inches deep at a rate of 100-120 compressions per minute. Continue until help arrives or an AED is available.

- Use an AED: If an AED is nearby, have someone retrieve it. As soon as it arrives, turn it on and follow the voice prompts. Do not be afraid to use it—the device will only shock if a shockable rhythm is detected.

- Resume CPR: Immediately after the shock, resume CPR. Do not stop to check for a pulse or breathing—just continue CPR until the device prompts another analysis or emergency personnel arrive.

Recovery After Surviving Cardiac Arrest

People who survive ventricular fibrillation and cardiac arrest face a recovery process that involves both physical and neurological healing.

If blood circulation was restored quickly with minimal brain injury, recovery can be excellent. Many people return to their previous lives with few or no limitations.

If brain injury occurred from prolonged arrest, recovery is more complex. Some may regain full function over weeks to months. Others may have permanent neurological deficits ranging from mild memory problems to severe disability. Targeted temperature management (cooling the body) is often used after cardiac arrest to reduce brain injury and improve outcomes.

Physical rehabilitation helps survivors regain strength and function, as many feel weak after a prolonged hospital stay. Emotional recovery is also challenging, as survivors often struggle with anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress. Counseling and support groups can help you cope with this life-changing event.

An ICD is implanted before discharge for most survivors, providing crucial protection against future episodes. Regular follow-up with your cardiologist is essential to monitor your ICD and manage your overall heart condition. Most survivors can eventually return to work, drive, and resume normal activities, offering a strong sense of hope for the future.

Key Points

To help you quickly remember the most critical information and steps, here are the key points about ventricular fibrillation and the necessary life-saving actions you need to know:

- Ventricular fibrillation is a chaotic heart rhythm where the lower chambers quiver uselessly instead of pumping. Circulation stops immediately, causing cardiac arrest and loss of consciousness within seconds.

- This rhythm causes the vast majority of sudden cardiac deaths. Without immediate treatment, it is fatal within minutes.

- Defibrillation—delivering an electrical shock to the heart—is the only effective treatment. The sooner defibrillation occurs, the better the survival. Each minute of delay reduces survival by 7-10%.

- CPR maintains some blood flow to the brain and heart until a defibrillator arrives but cannot convert ventricular fibrillation to normal rhythm by itself. Both CPR and defibrillation are necessary for the best outcome.

- Automated External Defibrillators (AEDs) can be used by anyone and have simplified the delivery of life-saving shocks. These devices provide voice prompts guiding users through every step.

- Bystander response is critical. Immediate recognition of cardiac arrest, calling emergency services, starting CPR, and using an AED when available creates the chain of survival that maximizes the chance of good outcomes.

- Common causes include heart attacks, previous heart damage, severe heart failure, cardiomyopathy, and inherited electrical disorders of the heart.

- Survivors of cardiac arrest from ventricular fibrillation typically receive Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillators (ICDs) that automatically treat future episodes, preventing death from recurrence.

- The best outcome occurs when ventricular fibrillation is treated within the first 1-2 minutes. This is only possible with immediate bystander action and readily available defibrillators.

Learning CPR and knowing where nearby defibrillators are located can help you save a life. When someone collapses in cardiac arrest, every second counts—immediate recognition and action mean the difference between life and death.

You may also like to read these:

Reference: Ventricular Fibrillation (VFib)