The aortic valve sits between the left ventricle and the aorta, the main artery carrying blood to the rest of your body. When it opens fully and closes tightly, blood flows forward smoothly with every heartbeat. But when the valve becomes too narrow (aortic stenosis) or too leaky (aortic regurgitation), the heart must work harder to push blood through or prevent it from flowing backward. Over time, this added strain weakens the heart and leads to symptoms such as breathlessness, chest discomfort, and reduced exercise tolerance. Aortic valve disease can arise from age-related calcification, congenital valve abnormalities, past infections, or connective tissue disorders.

Overview

Aortic valve disease includes two main problems: aortic stenosis, where the valve becomes stiff and narrow, and aortic regurgitation, where it fails to close completely and allows blood to leak backward. Some people develop both narrowing and leakage.

In a healthy heart, the aortic valve opens widely during each heartbeat to let blood exit the left ventricle and closes tightly to prevent backward flow. With disease, the valve may thicken, calcify, deform, or stretch, making it difficult to open or close properly. As aortic stenosis progresses, the heart must generate much higher pressure to push blood past the narrow opening. As aortic regurgitation worsens, the left ventricle must accommodate extra blood returning from the aorta, leading to enlargement and weakening.

Aortic valve disease can remain silent for years, particularly in its early stages. However, once symptoms occur—especially with aortic stenosis—they signal that the heart is struggling, and timely treatment becomes essential. Without intervention, severe aortic stenosis can be life-threatening, while progressive regurgitation eventually leads to heart failure if untreated.

Causes

Aortic valve disease develops from several underlying processes that alter the structure and function of the valve.

- Age-related calcification is the most common cause of aortic stenosis in older adults. Over decades, calcium deposits accumulate on the leaflets, making them stiff and preventing them from opening fully. This degenerative process resembles “hardening” of the valve.

- Bicuspid aortic valve is a congenital condition where the valve has two leaflets instead of three. Present in about 1–2% of the population, it causes earlier wear, leading to stenosis or regurgitation often decades before normal valves fail. Many patients are diagnosed in their 30s to 60s when symptoms develop or during routine imaging.

- Rheumatic fever, though much less common today in developed countries, can cause scarring, thickening, and fusion of valve leaflets. This leads to stenosis, regurgitation, or a combination of both.

- Aortic regurgitation can also result from disorders affecting the aorta itself. Conditions such as Marfan syndrome, Ehlers–Danlos syndrome, or long-standing high blood pressure can cause enlargement of the aortic root, stretching the valve and preventing tight closure.

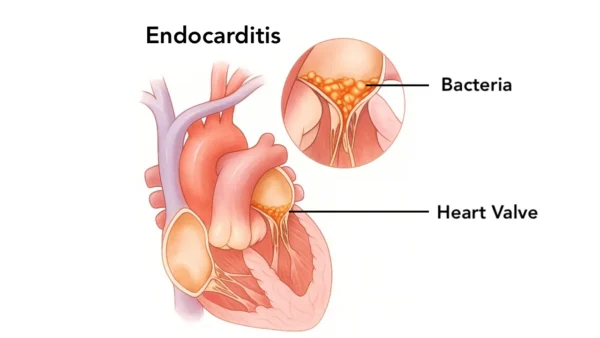

- Infective endocarditis damages the valve tissue through infection. This can create acute, severe regurgitation requiring urgent treatment.

- Other less common causes include chest radiation exposure, inflammatory diseases like ankylosing spondylitis, and trauma.

Symptoms

Symptoms depend on whether the problem is narrowing, leakage, or both—and how advanced it is. Early disease is often silent.

- In aortic stenosis, symptoms typically appear gradually but signal severe disease once they develop. Shortness of breath with exertion, chest pain or pressure (especially during activity), dizziness, or fainting spells are classic signs. Fatigue, reduced exercise tolerance, or feeling easily winded may also occur. Syncope (fainting) during exertion is particularly concerning.

- In aortic regurgitation, the heart compensates for years by enlarging and pumping harder. Symptoms usually appear later and include shortness of breath, especially when lying down, awareness of strong or pounding heartbeats, fatigue, or ankle swelling. Rapid worsening of symptoms can occur with acute regurgitation, such as from valve infection.

Because symptoms often develop slowly, patients may gradually limit their activities without realizing how much the disease has progressed. Paying attention to subtle changes in stamina or breathing is important.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis begins with a detailed history and physical exam. A characteristic heart murmur often raises initial suspicion. To confirm the diagnosis and assess severity, echocardiography is essential. This ultrasound shows how the valve opens and closes, the degree of narrowing or leakage, and how the heart chambers are adapting.

An electrocardiogram may show thickening of the heart muscle or rhythm abnormalities. A chest X-ray can reveal enlargement of the heart or aorta. In certain cases—especially when preparing for valve replacement—CT scanning provides crucial information about calcium buildup and aortic anatomy.

Exercise testing may help evaluate symptoms and guide treatment decisions in people who feel well but have moderate or severe stenosis.

Once diagnosed, regular follow-up imaging is critical. Aortic valve disease can progress unpredictably, and monitoring ensures treatment occurs at the right time—ideally before the heart becomes permanently weakened.

Treatment

Treatment depends on the severity of the valve disease, your symptoms, and how your heart is responding.

Medications can relieve symptoms but do not fix the valve. Diuretics may reduce congestion, and blood pressure medications help reduce stress on the heart—especially in aortic regurgitation. Treating risk factors such as hypertension, high cholesterol, and smoking slows progression of disease affecting the aorta.

For severe aortic stenosis, the only effective treatment is valve replacement. Two main options exist:

- Transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR), A minimally invasive procedure performed through arteries in the leg. It is often used for older adults or those at higher surgical risk, though it is increasingly used in younger and lower-risk patients. Recovery is typically quick.

- Surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR), A traditional open-heart surgery where the diseased valve is removed and replaced with a mechanical or bioprosthetic valve. It remains the preferred treatment for younger patients, those needing additional cardiac procedures, or people with anatomy unsuitable for TAVR.

For aortic regurgitation, surgery is recommended when symptoms develop or when imaging shows the left ventricle is enlarging or weakening—even if you feel well. Valve repair is possible in select cases, but replacement is more common.

Treating aortic root enlargement may require specialized surgery to replace part of the aorta and the valve together.

What Happens If Left Untreated

Severe aortic stenosis is life-threatening once symptoms appear. Studies show that after the onset of symptoms—especially chest pain, fainting, or shortness of breath—survival sharply declines without valve replacement.

Untreated aortic regurgitation eventually leads to progressive enlargement and weakening of the left ventricle, resulting in heart failure. Symptoms such as fatigue, breathlessness, swelling, and arrhythmias develop as the heart struggles to compensate.

Both conditions significantly increase the risk of sudden cardiac death, especially in advanced stages.

Timely treatment prevents these outcomes and allows most patients to return to normal activities with excellent long-term prognosis.

What to Watch For

Shortness of breath, reduced exercise tolerance, chest pressure, dizziness, or fainting—especially during activity—require prompt medical attention. A sensation of pounding heartbeats or awareness of your pulse may indicate worsening regurgitation. New swelling in the legs, rapid weight gain from fluid retention, or episodes of palpitations should also be evaluated.

Even mild or gradual changes matter, as early intervention leads to far better outcomes than waiting until symptoms become severe.

Living with Aortic Valve Disease

Many people with aortic valve disease live active, fulfilling lives, especially with regular follow-up and timely treatment. Routine echocardiograms help track progression. Maintaining a heart-healthy lifestyle—controlling blood pressure and cholesterol, exercising regularly, eating a balanced diet, and avoiding smoking—reduces strain on the heart and supports long-term health.

After valve replacement, most people experience significant improvement in symptoms and stamina. Activity restrictions vary depending on the type of valve and procedure, but many return to full activity, including exercise and travel, within weeks.

Lifelong follow-up with a cardiologist remains essential. People with mechanical valves take blood thinners, while those with bioprosthetic valves require periodic monitoring for wear. TAVR valves also require surveillance to ensure durability.

With modern treatments, long-term outcomes for aortic valve disease are excellent.

Key Points

- Aortic valve disease includes aortic stenosis and aortic regurgitation. Stenosis causes narrowing and obstructed flow, while regurgitation causes backward leakage.

- Diagnosis relies on echocardiography, which shows valve structure, severity, and the heart’s response. The disease can remain silent for years before symptoms appear.

- Severe aortic stenosis requires valve replacement—either TAVR or surgical. Aortic regurgitation also requires surgery once symptoms appear or the heart begins to enlarge.

- Without treatment, both conditions can lead to heart failure, arrhythmias, or sudden death. Timely intervention dramatically improves survival and quality of life.

- With proper follow-up, lifestyle measures, and modern valve therapies, most people with aortic valve disease can lead long, active, and healthy lives.

You may also like to read these:

Reference: Aortic Valve Disease